Partition cast a shadow over the island of Ireland that stretched across the 20th century. Less well known, however, is the fallout caused by the division of the Protestant population in Northern Ireland, a region known as Ulster. Of the 9 historic Ulster counties, only 6 remained in the United Kingdom. What became known as the three lost counties of Ulster–Donegal, Cavan, and Monaghan–were merged into the newly created Irish state. In the Lost Countries of Ulster: Loyalism and Paramilitarism Since 1920, University College Dublin Professor Ed Burke argues that we can’t understand the failure of Dublin and Belfast to forge closer ties without considering the lost counties. We also can’t fully appreciate the challenge of forging a multiethnic Irish state without recognizing how the people of the lost countries remained objects of enduring suspicion and distrust rooted in memories from the past. Last, we also need to recognize how lost county family ties played a part in the 1998 Good Friday Agreement that ended decades of intercommunal violence.

A shared Ulster identity has its roots in the history of Protestants from Scotland and England who settled in Northern Ireland in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This was a deliberate strategy of political consolidation and control over a region conquered by the Tudor monarchy. The Ulster plantation referred to the seeding of the region with Protestants as a bulwark against the largely Catholic population. Long before the creation of an actual border or even an Ulster identity, there developed a frontier mentality among the transplants to the region. This was an identity characterized by a strong sense of cultural pride, a militant attachment to a Protestant heritage, and a deep sense of belonging to a unique Ulster community that was neither Irish nor British.

Protestants living in the three counties had no inkling that they would be abandoned by their Ulster kin. Together they had signed the Ulster Covenant in 1912 taking a united stand against the British Government’s proposed home rule bill for Ireland that same year. They fought and died together in World War I, they joined the same Ulster clubs and the paramilitary Ulster Volunteer Force to fight against Irish independence (1910-1921). But despite the some 70,000 Protestants who lived in these countries, a greater proportion of Protestants than in the other 23 countries that became the Republic of Ireland, they were never less jettisoned from Ulster. This was based on the conviction that incorporating the large number of Catholics who lived in these three countries would dangerously dilute Protestant strength in Northern Ireland. This decision, however, narrowly defined Ulster identity along religious lines, excluding Catholics who may not necessarily have wanted to break with the United Kingdom.

It was generally wise for Ulster loyalists who remained in the three counties, and their descendants, to engage in a deliberate, public forgetfulness of their community’s resistance to Irish nationalism and republicanism. After all, violent sectarianism flared repeatedly in Ulster throughout the twentieth century and Protestants in the southern border counties became convenient for retribution when Catholics were targeted in the north. However, a disinclination to remember, out of self-preservation, or a desire not to offend neighbors by revisiting painful feuds, is not the same as amnesia. Memories can be passed on, but only in a setting of trust and mutual understanding. Edward Burke, Ulster’s Lost Counties: Loyalism and Paramilitarism since 1920.

Despite the decision to shrink North Ireland, the three lost countries remained loyal to Ulster and played a pivotal and largely forgotten role in the Irish Civil War. With the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty (1921) and the creation of an Irish Free State as a Dominion within the United Kingdom, the British Army withdrew from the border region leaving the protestant populations of Donegal, Cavan, and Monaghan exposed and at risk. Well armed and organized and with the largest Protestant population of the three lost counties, Monaghan was successful in fending off the advances of the Irish Republican Army. Lost county resistance, at least in the short term, may have contributed to the loyalist preference for the Irish Free State’s status as a dominion within the United Kingdom.

Just as Monaghan loyalists checked the threat of the IRA, so did loyalists in Donegal. The major contribution of Donegal loyalists was to the city of Derry across the border in Northern Ireland. Catholic Nationalists were in the majority in Derry. With only a small British military presence at the start of the Civil War, Derry was very much at risk of falling to the IRA. It was the willingness of Donegal loyalists to take up arms in support of their Ulster kin in Derry that helped turn the tide against the IRA. Ed Burke argues that decades later there remained a deep sense of debt and gratitude among unionists in Northern Ireland toward loyalists in Donegal for their role in the Civil War.

Of the three lost counties loyalists in Cavan suffered least from the violence of the Civil War. This in part had to do with the internecine conflict between the IRA and their Hibernian rivals that was especially intense in Cavan. But it also stemmed from the fact that the Protestant population was much more dispersed in Cavan compared with Monaghan and Donegal. This complicated efforts to organize and may have reduced the incentive to take action. Where loyalists from Cavan were most active was in the service of the police in Northern Ireland. Police recruitment for the Royal Irish Constabulary was highest in Cavan and police officers from Cavan wielded considerable power in Northern Ireland.

Without considering the lost counties it is impossible to understand the nature of violence in Ireland during the Civil War. Violence was far more sectarian and indiscriminate in the north than in the Irish Free State. A far greater number of civilians died in the fighting in the north. For example, 85% of those who died in the Ulster county of Antrim compared with 45% in Dublin between 1919 and 1921 were civilians. Between 1920 and 1920 Belfast suffered between 409 and 498 fatalities and between 1200 and 2000 wounded. The vast majority of these casualties were Catholics, even though they represented only one third of the city’s population.

Despite what Ed Burke notes as the absence of scholarly attention, three-county Protestants who moved to Northern Ireland were instrumental in fueling the sectarian violence. They did so by taking up officier class and rank and file positions within various paramilitary and police organizations in the north. Perhaps the most prominent examples were Cavan loyalists John Nixon and William Coote. Burke describes Nixon and Coote as « representative of an uncompromising Protestant tradition along Ulster’s southern frontier. » Burke argues that the tandem of Nixon and Coote played a central role in sabotaging the efforts of Sir James Craig, the first Prime Minister of Northern Ireland (1921-1940), to forge closer ties between Belfast and Dublin and to reform the Royal Ulster Constabulary by including a larger number of Catholics.

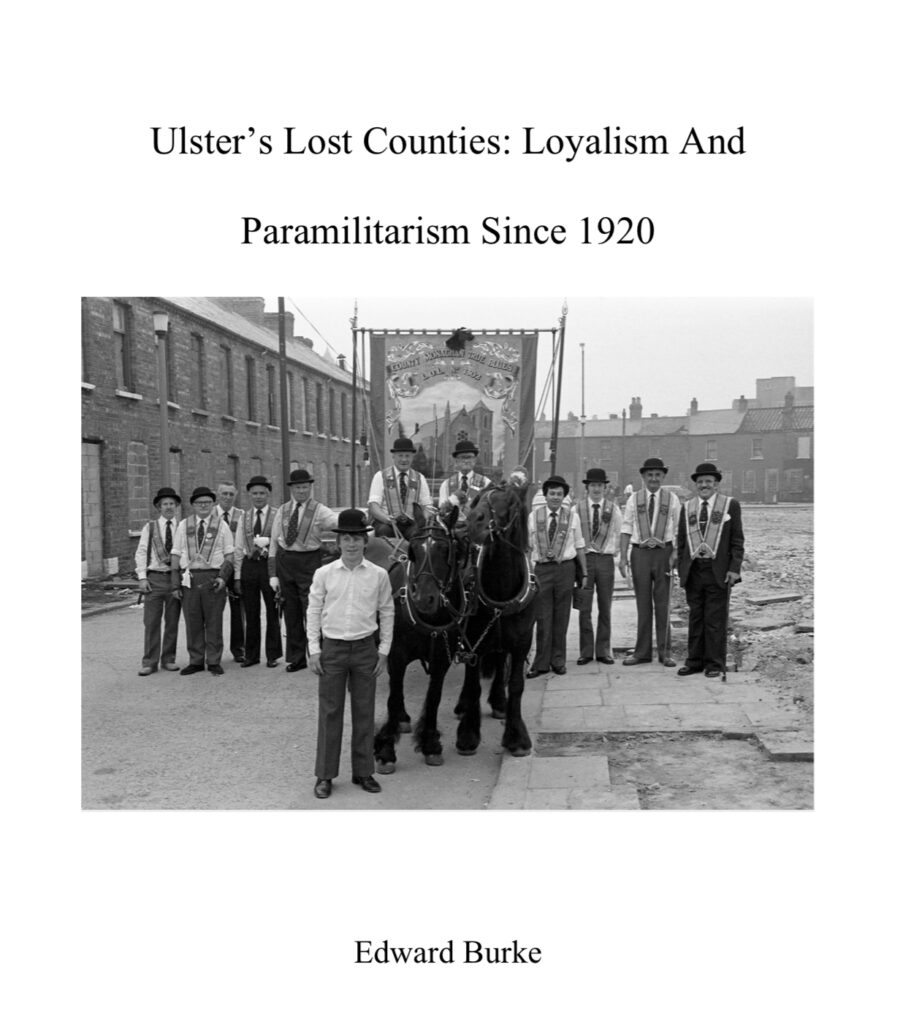

In the decades after the partition thousands of three county loyalists migrated to Northern Ireland. They set up lodges like the Loyal Sons of Donegal and County Monaghan True Blues in an effort to preserve the memory of their roots in the lost counties. The memory of the lost counties continued to exert an influence on voters in places like Belfast. In this working class community unionists rejected traditional business and upper class elites who dominated Northern Irish politics in favor of politicians with a three county connection. John Nixon would hold a seat as an MP in the Stormont parliament for two decades until his death in 1949. Other aspiring politicians, like Jim Kilfedder, used his mother’s roots in Donegal as political capital in his election as an MP in 1964.

Some of the first sparks of thirty years of violence between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland known as the Troubles originate in the memory of the lost counties. In the 1960s, the town of Caledon, near the border of Monaghan, became the focal point of American Civil Rights inspired protests by Catholics against discriminatory housing policies favoring Protestants. Protests erupted over particularly glaring cases of discrimination, such as the eviction of a Catholic family squatting a residence at Kinnard Place so it could be made available to a single Protestant woman. Lost in this story is the fact that two thirds of Caledon’s residents came from Monaghan. Bearers of the memory of discrimination and forced removal, many lost county Protestants in Cadelon were staunch supporters of favoring loyalists.

As the violence of the Troubles escalated, memories of the past also surfaced across the border to haunt Protestants who remained in the lost counties. Decades after the end of the Irish Revolution and Civil War lost county Protestants continued to be regarded with suspicion and distrust. Perhaps the most glaring case is that of Billy Fox. While Fox’s ancestors had signed the Ulster Covenant and had been staunch supporters of loyalist resistance to Irish independence, Fox himself was a shining example of post partition Protestant assimilation into the newly created Republic of Ireland. Elected as a TD for the Fine Gael party Fox hoped to use his energy for the betterment of the Republic of Ireland. Yet as with other politicians whose ancestors were loyalists, Fox continued to be slandered and suspect because of memories from the past. While visiting his fiancée’s home in Monaghan Fox was gunned down by members of the IRA, the only sitting member of parliament in Ireland to be killed during the Troubles.

Ironically, if lost county memories continued to divide and fuel violence decades after partition, they may also have contributed to the Good Friday Agreement and the end of the Troubles. During the 1990s then Prime Minister Tony Blair was particularly focused on bringing peace to Northern Ireland. Ed Burke credits this in no small part to Blair’s own ancestral roots in the lost countries. Blair’s mother’s family, the Corscadens, were from Donegal, relatives he often visited during his childhood and as a young adult. Then Democratic Unionist Party leader Ian Paisley commented that Blair’s Ulster roots were an important trust building factor in Paisley’s willingness to endorse a power sharing agreement that became the 1998 Good Friday Agreement. By agreeing to share power with the nationalist Sinn Féin party, the Good Friday Agreement has succeeded in ending decades of conflict in Northern Ireland.

Edward Burke

Edward Burke is an Assistant Professor in the History of War since 1945 at University College Dublin (UCD). He is currently the Director of the International War Studies MA programme and Director of Graduate Teaching at the School of History. He is the author of Army of Tribes: British Army Cohesion, Deviancy and Murder in Northern Ireland (Liverpool University Press, 2018), Ghosts of a Family: Ireland’s Most Infamous Unsolved Murder, the Outbreak of the Civil War and the Origins of the Modern Troubles (Merrion Press, 2024), Ulster’s Lost Counties: Paramilitarism and Loyalism since 1920 (Cambridge University Press, 2024).