The Great Patriotic War, shorthand for the war against Nazi Germany, has become the focal point of Russian nationalism under Vladimir Putin. Memories of the war bolster the legitimacy of Putin’s grip on power while offering Russians a feel good narrative about their national past. Rather than reducing the celebration of the Great Patriotic War to top down politics of memory, Pennsylvania State University Professor Katya Haskins argues that we need to consider the role of and appeals to family memory. Raised in Russia during the Soviet era and graduating from the prestigious Moscow State University at the end of the Soviet period, Katya highlights how family memories of the war span regime changes. A sense of duty and obligation to remember the sacrifices of the war generation are deeply rooted sentiments that Putin can exploit in the present. Notions of patriotic sacrifice for the motherland, ingrained through popular culture, make Russians willing consumers of today’s Hollywood style high voltage depictions of the war. Rather than being indoctrinated from above, Russians are active and eager participants in the politically charged memories of the war.

Katya’s high school years overlapped with the era of greater openness about the past during the Gorbachev era. She feels fortunate to have lived through this era when the dark spots of the Soviet past came under public scrutiny and long established patriotic narratives lost political currency. In my interview she recalled how her high school history exams were shelved in favor of a less problematic Soviet sociology test. Despite the turbulence and upheaval of the Gorbachev years and the start of the Yelstin presidency, memories of the Great Patriotic War never entirely faded from view. To shore up his own popularity, it was Yeltsin who revived the Soviet tradition of grandiose May 9th military parades to celebrate the victory over Nazi Germany.

Katya uses the concepts of mnemonic habituation and mythical logics of remembrance to explain how family memories carry over from the Soviet to the Putin era. Mnemonic habituation refers to memory habits or ways in which memories are ingrained in us through repetitive actions. Russians today have no first hand, lived memories of the war. Instead, memories of the past are imprinted or embodied through participation in ritual-like commemorations. The commemorations of the past could include everything from participating in annual memorial events or watching classic war films that air during significant patriotic dates on the national calendar. Much like putting one’s hand over one’s heart and singing the national anthem at the start of a baseball game, mnemonic habituation is a collective form of embodied remembrance.

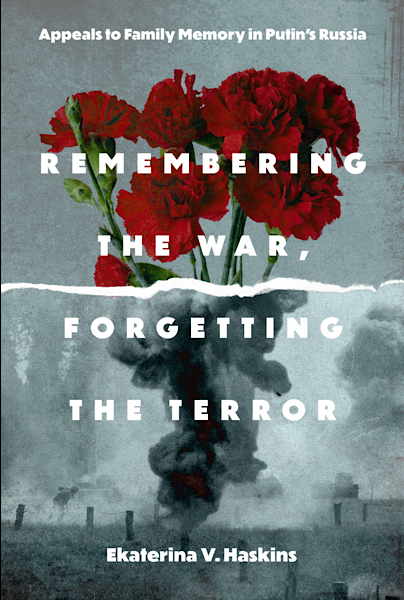

How people remember their collective past also shapes their predisposition to support or oppose wars waged by governments on their behalf. In Russia, the memory of the “sacred” war against an external enemy—rather than the remembrance of the Soviet state’s violence against ts own citizens—has formed the emotional grounds for popular support of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. Ekaterina V.Haskins, Remembering the War, Forgetting the Terror: Appeals to Family Memory in Putin’s Russia.

Mythical logics of remembrance refers to long established taboos and duties. We are tradition bound, for example, to elevate the acts and deeds of our ancestors in our memory. Casting aspersions on our forebears is always possible but presents the very real risk of making us look like ingrates. It is for this reason that when eulogizing the departed we are typically careful to edit out memories that might cast them in an unfavorable light. In the case of the World War II generation, Russians are naturally inclined to remember the sacrifices of their ancestors. By the same token, the weight of celebratory memories of the past tends to drown out or silence the millions who suffered from Stalin era repressions. In short, if the Putin regime choses to accentuate the heroism of the generation that defeated Nazi Germany while forgetting the repressions, this form of selective remembering resonates with the mythical logics of remembrance of the Russian people.

Terms such as motherland, fatherland, or homeland are part of the litany of ways nations attempt to naturalize the bonds of citizenship by borrowing from the language of family ties. Efforts to bolster national ties can similarly function through appeals to family memory. Rather than simply mandating and imposing a narrative of the national past, citizens can be beseeched to remember the sacrifices of the generations that came before then or those that will follow. This kind of appeal to family memory resonates powerfully because it goes to the heart of our duty to remember. Appeals to family memory are so influential because they are so difficult to question or challenge, especially at a time when we are consumed by the desire to document and preserve our family histories.

The memory of the Great Patriotic War is an irresistible resource for Putin’s Russia for the same reason it was so attractive to the Soviet Union. With over twenty million Russians who died in the war, it was an experience that affected most families. Proud memories of the victory over Nazi Germany, not unlike American pride in the Greatest Generation, continue to be widely shared in Russia today. By appealing to family memory, Putin’s regime can lend greater authenticity and legitimacy to what has become the cult of the Great Patriotic War. Moreover, as Katya Haskins notes, by placing the emphasis on the victory over Nazi Germany, memories of the war can exclude the less convenient memories of Stalin’s repressions. In short, the memory of the Great Patriotic War in Russia today is an exercise in both remembering and forgetting that works in close connection with Russian families.

Movies are an important example of mnemonic habituation. Critically acclaimed classic war films, such as Andrei Tarkovsky’s Ivan’s Childhood (1962), Larissa Shepitk’s The Ascent (1977) and Stanislav Rostotsky’s The Dawns Here are Quiet (1972) conveyed themes and ideals that supported state narratives without ever being overt forms of propaganda. Appearinging annually on television on significant dates on the official memory calendar, such as the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany on June 22 or Germany’s surrender on May 9th, these films became powerful vectors of patriotic sentiments. Absorbed within a family setting and reinforced through repeated viewings, themes such as patriotic self sacrifice could be more easily and effectively internalized and unquestionably accepted.

Modern war films use Hollywood blockbuster techniques to appear to younger audiences. Released in 3D the 2013 film Stalingrad showcases all the action packed, special effects charged content of any Hollywood film. From super slow motions scenes of hand to hand combat and bullets slicing through the air to panoramic shots of soldiers, military hardware, and a shattered cityscape, the images and drama of Stalingrad would be familiar to any contemporary moviegoer eager for a cinematic adrenaline fix. Yet while these films are updated for the video game generation the themes of soldiers selflessly sacrificing themselves for the motherland are part of a long and familiar tradition going back to Soviet times. It is the accumulated weight of the patriotic sentiments featured in these films that helps give weight to the state sponsored celebrations of the Great Patriotic War today.

Russian war films have also acquired the ability to perform a powerful disappearing act. They are at once able to incorporate stories of state oppression and the suffering of ordinary Russians while at the same time overshadowing that memory with a larger story. Remakes of films like Dawns Here are Quiet (2015) or the television miniseries The Penal Battalion (2004) tell the story of both women and men whose lives have been shattered by the oppressive years of Stalin’s rule. Yet the overriding message is not one of victimization, anger or resentment but rather celebration. Despite all they have suffered, the characters in these productions still embrace the motherland and are willing to sacrifice everything for their country. It is through their willingness to give their lives to defend their country that these films elevate the characters to heroic status while minimizing the memory of the repressions.

Efforts on the part of the Russian people to commemorate the Great Patriotic War in their own way, especially when successful, are always at risk of being hijacked by the state. Perhaps the best example is the Immortal Regiment. Started in the region of Tomsk in 2011, the original idea was to break with excessive forms of commemoration of Victory Day. A grassroots initiative, the Immortal Regiment was intended to include all those affected by the war, even those who experienced Stalin’s repressions. Their commemorations were supposed to be more subdued, devoid of the flag waving ultra patriotic exuberance of traditional Victory Day celebrations. In the end, a pro-state copycat organization copyrighted the name and turned the event into the opposite of what its originators had intended. Participants are now encouraged to dress in war-era military garb, sing patriotic songs and are given photos of their World War generation ancestors that they can carry in what has become an ever lavish commemoration.

Perhaps the freest space for commemorating the war is the digital one. But even here we see the power of the state to expropriate or punish initiatives that are regarded as too provocative. For example, the human rights organization Memorial, originating at the end of the Soviet era, made its reputation through its efforts to record and preserve a record of Stalin’s victims. Not only was Memorial shuttered by Putin’s regime, its name was adopted by an online initiative to encourage Russian participation in a digital commemoration of the war. Other organizations that have been overly critical, such as the Immortal Barracks, have been sanctioned and their leaders have fled into exile. It remains to be seen whether projects like Open List, that attempt a less provocative approach to commemoration, can succeed in avoiding the ire of the state.

The militarization of Russian society began long before the invasion of Ukraine. From increasingly lavish Victory Day commemorations to Cathedrals, military theme parks and museums, Putin’s regime has undeniably devoted considerable resources to what has become the cult of the Great Patriotic War. Yet it would be a misconception to regard Russians as mere pawns of the state. Generations of cultural conditioning stretching back to Soviet times, make Russians susceptible to nationalist themes in the present. An understandable reverence and deep regard for the sacrifices of their wartime ancestors make state messaging about the past all the more appealing. From the Immortal Regiment to digital memory projects, independent memory initiatives that might broaden the understanding of the past frequently succumb to state expropriations or sanctions.

Ekaterina V. Haskins

Ekaterina V. Haskins is a Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences and Visual Studies at Pennsylvania State University. She is the author of three monographs, including Popular Memories: Commemoration, Participatory Culture, and Democratic Citizenship (The University of South Carolina Press, 2015) and Remembering the War, Forgetting the Terror: Appeals to Family Memory in Putin’s Russia (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2024) as well as numerous articles on rhetoric, memory, and visual culture.