Despite the removal of scores of prominent monuments to the Confederacy the vast majority remain firmly in place. For communities to make informed decisions about the future of these monuments they need to have a clear understanding of their past. It was with this objective in mind that University of North Carolina at Charlotte historian and professor emerita Karen L. Cox wrote No Common Ground: Confederate Monuments and the Ongoing Fight for Racial Justice. Cox shows that these monuments worked in tandem with Jim Crow laws and racial terror to build a system of white supremacy that lasted another hundred years after the end of slavery. These monuments, and the middle and upper class southern women behind them, instilled generations of white southerners with a firm belief in the righteousness of the Lost Cause and the need to resurrect and perpetuate a system of white domination.

Southern men returning from the Civil War broken and defeated were in no position to celebrate themselves. It was middle and upper class white southern women who took on this role by transitioning from their wartime support work, forming Ladies Memorial Associations and taking up the task of repatriating fallen soldiers and erecting tombstones and monuments in cemeteries. In record time after the departure of occupying Federal troops, this memorial work moved from cemeteries to public spaces and took on a whole new magnitude. In the case of Augusta, for example, in 1875, just four years after Federal troops left the city, the Ladies Memorial Association helped raise the money to erect a seventy-six-foot-tall monument to the Confederacy in the center of the town. A harbinger of future unveiling ceremonies, some 10,000 people participated in the event.

In addition to the parades and crowds, unveiling ceremonies involved numerous speakers who were afforded the opportunity to elaborate on the Lost Cause narrative of the Civil War. First articulated by the Virginia native and wartime journalist Edward A. Pollard in his 1866 book The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates, the Lost Cause offered a story of redemption for white southerners. Pollard cast the war as a noble struggle on the part of the South to preserve a righteous culture. Pollard defended slavery as a part of a civilizing mission to Christianize and socialize the “African race.” Africans were fed, clothed, and cared for, he argued, in ways that far surpassed the treatment of workers in the North who suffered from the condition of wage slavery. More true to the states rights spirit of the founding fathers, white southerners, Pollard believed, were superior in almost every way to northerners. Southerners may have lost the war, but they could still defend the superiority of their race and culture.

If the unveiling of Confederate monuments became a more grandiose public event starting in the 1870s, it was beginning in the 1890s to World War I that their numbers multiplied exponentially. Karen Cox notes that 200 monuments were built between 1900 and 1910 with 48 monuments constructed in the peak year of 1911 alone. This was the period when the United Daughters of the Confederacy took center stage. Created in 1894, the UDC raised the equivalent of millions of dollars in today’s money to fund the design, construction, and the elaborate unveiling ceremonies surrounding these monuments. With some 100,000 members by World War I it was the social network of the UDC which made it so effective. Husbands, fathers, brothers and close acquaintances of UDC members in positions of power and influence in the private and public sectors were tapped to support the organization’s work. Decades before women received the right to vote, the women of the UDC carved out a powerful role in the public sphere.

While the monuments to the Confederacy honored the struggles and sacrifices of the past they were intended to make a statement about the present. Deliberately placed in public squares and especially on courthouse lawns, monuments to the Confederacy clearly placed these spaces of common ground under the authority of white southern men. At the same time these markers of white power and authority were being erected, white southern men were reclaiming the reigns of power in courthouses and state capitals. Legislators, sheriffs, and judges used their power to roll back the gains of Reconstruction and to create a new caste order. Within this system African Americans were removed from public offices, deprived of the right to vote, and relegated to Indian-like Dalit or untouchable status. For those who challenged or forgot their place, lynching was part of a system of racial terror that claimed thousand of lives in medieval style horrific public murders intended to maintain the new social order. To truly grasp the purpose and context within which monuments to the Confederacy were built, Cox stresses that we need to understand how they worked in tandem with the political and racial terror of the Jim Crow South.

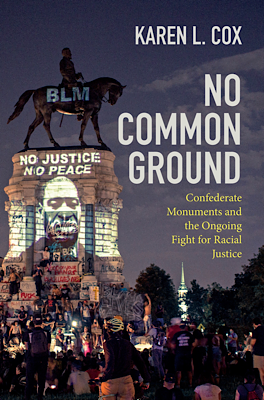

Confederate monuments are not innocuous symbols. Though in the past they were used by white southerners to teach about a mythological noble heritage completely stripped of the story of slavery, what they “teach” is not history. They are weapons in the larger arsenal of white supremacy, artifacts of Jim Crow not unlike “whites only” signs that declared black southerners to be second-class citizens. Karen L. Cox, No Common Ground: Confederate Monuments and the Ongoing Fight for Racial Justice.

Not only did white northerners fail to denounce these efforts to put the Confederacy on a pedestal they were complicit in the process. A quick perusal of contemporary southern periodicals reveals the many ways in which white northern-run businesses found economic opportunities in the nostalgia for the Civil War era and antebellum South. The pages of the Confederate Veteran from the early twentieth century, for example, are replete with advertisements from northern businesses hawking everything from confederate grave markers to uniforms. Many of the firms that designed and built monuments to the Confederacy were located in the North. The South may have lost the war but won the narrative, as historians have pointed out, but northern businesses certainly profited along the way.

Those who were quite vocal about the dangers of Confederate monuments were African Americans. Both Frederick Douglas and W.E.B. Du Bois used their public influence to decry the threat of the Lost Cause narrative and the rewriting of the recent past. As early as the 1870s, Frederick Douglas referred to the praise that followed Robert E. Lee’s Death as “nauseating flatteries.” Du Bois commented that a better inscription on monuments to the Confederacy would be “Sacred to the Memory of those who Fought to Perpetuate Human Slavery.” Early on black-run newspapers were especially vocal in their criticism. In 1890 the Richmond Planet complained that Confederate veterans from all over the country were gathering for unveiling ceremonies and acting as if the South had never lost the war. The pages of the most prominent black newspaper, The Chicago Defender, were replete with criticisms and warnings about monuments to the Confederacy. In a 1920 article the Defender argued that “every Confederate monument standing under the Stars and Stripes should be torn down and ground into pebbles.”

Pressure to dismantle the Jim Crow system grew following the Second World War. Many African Americans were influenced by the Double V campaign launched by the Pittsburgh Courier calling for victory against facism abroad and victory against white supremacy at home. Harry Briggs was one such veteran who became the plaintiff in the case that led to the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision which outlawed segregation in public schools. The outrage sparked by the travesty of the 1955 Emmett Till murder trial and the gruesome photos of the young boy’s body encouraged more African Americans to take up the fight. Momentum grew as civil right protesters challenged a segregated store lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina in 1960 and tested Federal laws against racial segregation on interstate buses in 1961. In 1963 nearly a quarter million people gathered in Washington DC for the March on Washington to show their support for racial equality. Finally the landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, religion, color, sex and national origin and outlawed discriminatory voting practices in place in many southern states.

Just as there was a backlash against Reconstruction, southerners reacted forcefully against the changes taking place in the 1960s. In fact, white southerners framed the defense of segregation by recalling their efforts to fight back against the northern imposed system of Reconstruction. It was during this period that a number of southern legislatures voted to incorporate the Confederate battle flags into their state flags. Prominent southern political leaders, such as Alabama Governor George Wallace integrated themes from the Lost Cause into their defense of segregation. During the 1961-1965 Civil War Centennial southern states such as Missippissi poured hundreds of thousands of dollars into commemorative work. Between 1950 and 1969 Karen Cox estimates that some 33 new Confederate monuments were erected as well as scores of schools named after Confederate heroes.

Racial progress followed the civil rights achievements of the 1960s. During the period from 1980 to 2015 more African Americans attended college and rose to positions of political influence. With more of a presence and voice within the educational and political establishments it becomes possible for African Americans to object to the symbols and traditions devoted to the memory of the Confederacy. By the late 1980s major newspapers began to describe the Confederate battle flag as a symbol of racism. The NAACP began to call for the removal of Confederate battle flags from state houses and from state flags. In 1990 African American and former Charlotte Mayor Harvey Gantt unnerved the Republican establishment by narrowly losing in a senatorial race to long-time Republican powerhouse Jesse Helms.

It was in response to the campaign of Harvey Gantt that Republicans introduced a form of affirmative gerrymandering that successfully contained the black vote by consolidating them into smaller numbers of voting districts. Conservate white politicians who rose to power in the South in the 1990s and after became staunch defenders of Confederate symbols and used the fear of their removal to rally voter support. During this period when the growing influence of black political leaders came to be seen as a threat to Confederate symbols and heritage we see the creation of new white supremacist groups wielding both Nazi and Confederate battle flags in their marches and gatherings. New groups such as the League of the South became much more outspoken defenders for Confederate symbols.

It is within this escalating backlash to the racial progress that followed the civil rights era that a series of violent episodes ensued. In 2015 a white supremacist opened fire on a bible study group in a historic African American church in Charleston South Carolina murdering nine people. Social media pictures of the gunman wrapped in the Confederate battle flag circulated in the media sparking a national debate about Confederate symbols. In the aftermath of the massacre South Carolina governor Nikki Haley decided to remove the Confederate battle flag from the state capitol grounds. Similarly, it was the Charleston Massacre that swung New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu in the direction of deciding to remove four prominent Confederate monuments from the city. However many state legislatures in the South moved in the opposite direction enacting heritage protection measures designed to safeguard Confederate monuments.

In 2017 in Charlottesville Virginia tensions over Confederate monuments triggered a second violent episode. Protesters calling for the removal of the city’s Robert E. Lee statue came into conflict with far right groups and self proclaimed defenders of the monument. Within this turmoil one white nationalist drove his car into a crowd of peaceful protestors killing thirty-two-year-old Heather Heyer. Then President Donald Trump further fanned the flames by stating that “you had some very fine people on both sides.” Trump added that efforts to remove the Lee statue were a slippery slope that could lead to calls for the removal of statues of Washington or Jefferson. “Where does it stop,” Trump questioned.

The third violent episode came in 2020 with the brutal police killing of George Floyd. Videos of the white police officer immobilizing Floyd for nearly ten minutes with a knee on his neck ignited widespread anger about police violence targeting African Americans. The public outrage caused by the murder of George Floyd added fuel to the Black Lives Matter movement. Both nationally and internationally supporters of the movement focused their anger on vandalizing and toppling monuments to white supremacy. In the United States, the violent reaction to Confederate monuments can partly be understood as the result of historical preservation acts passed in the preceding years. These acts precluded the possibility of a more peaceful and constructive dialogue about the future of these monuments.

In some cities, such as Richmond Virginia or New Orleans Louisiana, where local authorities had jurisdiction, Confederate monuments were removed. This was by no means an easy process. In the case of New Orleans, it took seven different lawsuits and thirteen judges before the removal of four Confederate monuments from the city was possible. One of the contractors involved in the removal had his car blown up. Three of the monuments were removed in the dead of night and under police protection to reduce the threat of violence. When African American Devon Henry and his company, Team Henry Enterprise, accepted the contract to remove fifteen Confederate statues from Richmond’s Monument Avenue, he received death threats, had to carry a gun and wear a bulletproof vest to work.

While scores of monuments were toppled following the murder of George Floyd most are still standing. In deciding the fate of these monuments communities need to understand their history. They were originally built in tandem with Jim Crow laws and racial terror to establish a new system of white supremacy after the end of slavery. Following the Second World War, they were part of the fight against change and the struggle to preserve a system of segregation. When change proved inevitable, they were defended by those who felt threatened by the racial progress that came out of the civil rights era. From the outset, prominent African Americans leaders and black-run newspapers recognized the dangers of these monuments. It is time that we heed their warnings, reject the racial order these monuments were erected to create, and move toward a more democratic and inclusive future.

Karen L. Cox

Karen L. Cox is a historian and professor emerita at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. She is the author of Dixie's Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture, Dreaming of Dixie: How the South Was Created in American Popular Culture, Goat Castle: A True Story of Murder, Race, and the Gothic South, and No Common Ground: Confederate Monuments and the Ongoing Fight for Racial Justice.