Cambodia has often been cast as a broken, amnesiac nation, unable to confront the memory of the horrors it experienced during the Khmer Rouge era. How did these assumptions justify the establishment of transitional justice mechanisms such as the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC)? In what ways were the therapeutic claims of the ECCC overblown and destined to disappoint? How did the government of Cambodia use the ECCC to support its own self-serving reading of the past? What important memory work did NGOs take on that is often forgotten because of the tendency to focus exclusively on prominent institutions such as the ECCC? To answer these questions and more, listen to University of Bath sociologist Pete Manning, author of Transitional Justice and Memory in Cambodia: Beyond the Extraordinary Chambers.

Drawing from the work of French philosopher Michel Foucault, Manning notes ECCC was bound to disappoint because it was anchored in western assumptions about memory, trauma, and healing applied wholesale to nations. Cast as a broken, amnesiac nation, Cambodia was in need of the intervention of transitional justice to come to terms with its past. However, over twenty years ago, during his earliest visits to Cambodia, long before he embarked on his academic career, Manning recognized that Cambodians had never forgotten the genocide. How the genocide was remembered, such as a mother warning her child to finish a meal or the “Pol Pots might come to get them,” didn’t necessary conform to western therapeutic notions of working through traumatic memories.

Precisely because of its roots in western conceptions of memory and trauma, transitional justice mechanisms such as the ECCC, tend to make far reaching claims about the promise of healing by confronting the past. Not only do these claims fail to recognize the myriad ways in which real people remember and make use of the past, they also mask the political constraints that limit the possibilities of transitional justice. In the case of Cambodia, the government of Cambodia never gave the ECCC a blank check to investigate and prosecute the crimes associated with the Khmer Rouge. Approval and support for the ECCC were always contingent upon the trials focusing narrowly on the Khmer Rouge leadership. The aim of Cambodian authorities was to extend an olive branch, or blanket amnesty, to rank and file members of the Khmer Rouge. It was only when the later ECCC cases began to veer towards broader investigations of the Khmer Rouge that the government intervened and refused to cooperate.

Similarly, member states that supported the creation of ECCC had no intention for the court proceedings to look at the broader context that led to the rise of the Khmer Rouge. This was certainly true of the United States. It was the intensive bombing of Cambodia within the context of the Vietnam War that caused the deaths of tens of thousands of civilians and paved the way for the Khmer Rouge’s seizure of power. Delimited to the period of the Khmer Rouge’s time in power, from 1975 to 1979, the proceedings could not address Khmer Rouge violence after 1979 when it received support and recognition from the United States because of its opposition to Vietnam.

During the actual proceedings Khmer Rouge defendants did have an opportunity to take strategic positions in relation to the memory claims of the court. In some cases, such as that of Duch, charged in the first case with the killings associated with S-21 (Toul Sleng detention center in Phnom Penh), he attempted to acquiesce by accepting responsibility for his role in the killings while shifting ultimate authority to the Khmer Rouge leadership for the far more significant national calamity. In other instances, defendants attempted to deny accusations regarding their leadership role by pointing to the chaos of the period and the impossibility of maintaining a strong command structure. The violence that occurred was the result of the decisions made by lower level Khmer Rouge, not the leadership. Finally, by adopting a position of rupture, defendants tried to undermine the authority of the court by pointing out inconsistencies such as the failure to hold the United States accountable for the massive loss of life caused by the carpet bombing of Cambodia during the Vietnam War.

Cambodian communities continue to renegotiate varying relationships to memories of atrocity, often ambivalently or on registers that elide, jar with or are dislocated from the prevailing language of transitional justice and the normative injunction to remember at its heart. Peter Manning, Transitional Justice and Memory in Cambodia: Beyond the Extraordinary Chambers.

While international tribunals such as the ECCC are a core feature of transitional justice, they tend to overshadow the role of civil society and non-governmental initiatives. In the case of Cambodia, Peter Manning highlights the importance of two organizations—the Documentation Center of Cambodia or DC-Cam and the Transcultural Psychosocial Organization or TPO. DC-Cam, established in Phnom Penh in 1995, was an offshoot of Yale University’s Cambodian Genocide Program (CGP). The original mission of the CGP, supported by a grant from the United States Department of State, was to gather and safeguard evidence of the Khmer Rouge’s participation in the genocide for the purpose of future legal action. DC-Cam became an independent organization in 1997 and established the Sleuk Rith Institute, a documentation and research center. As stated on its website, the Sleuk Rith Institute is “dedicated to reconciling the destructive legacy of the Khmer Rouge with Cambodia’s enduring cultural heritage through a focus on the timeless values of justice, memory, and healing.”

The work of DC-Cam has evolved over time. In its early years it collected evidence of Khmer Rouge crimes from the mapping of mass graves to the identification of prison sites. DC-Cam recovered, organized and archived an extensive body of records from the Khmer Rouge government (Democratic Kampuchea). Many of the records and black and white photos from the infamous S-21 detention center in Phnom Penh were the result of work by DC-Cam. The driving force behind the work of DC-Cam is its executive director, Youk Chhang. Chhang is himself a survivor of the Khmer Rouge era who lost several family members to the violence. Since 2004 Chhang has spearheaded a massive public education program about the crimes of the Khmer Rouge and the prosecutorial work of the ECCC.

The opening page of the Transcultural Psychosocial Organization or TPO website points to Cambodia’s traumatic past as the reason for ongoing and pronounced mental health problems ranging from PTSD to suicide. Dialogue and truth telling are important instruments of the TPO’s efforts to promote reconciliation in Cambodia. In partnership with other programs, such as Youth for Peace, TPO has organized exchanges between former Khmer Rouge and its victims as part of a larger testimonial therapy approach to coming to terms with the past. As beneficial as this work may be, Pete Manning points out that the reliance on western scientific assumptions stips victims of agency, reducing them to traumatized subjects in need of healing and reconciliation, while denying legitimate demands for retribution or redress. This therapeutic approach to the past is very much in line with the directives of the state which seeks to limit blame for the past to the Khmer Rouge leadership while offering a blanket amnesty to the rank and file.

The most prominent sites of memory devoted to period of Khmer Rouge rule and the genocide in Cambodia tend to simplify and flatten the past. This is certainly true of S-21 or Tuol Sleng, the most infamous Khmer Rouge detention and torture center. By literally framing the genocide in black and white, as a story of victims and perpetrators, it is easier to cast the successor regimes in a heroic savior role. The black and white photos of Khmer Rouge violence on display at S-21 have become emblematic of the genocide in Cambodia. Yet many of these photos include former members of the Khmer Rouge who were themselves caught in the spiral of violence. The reality that the perpetrators one day could become the victims the next does not fit neatly within the official narrative that frames the past in terms of a good versus evil manichean binary.

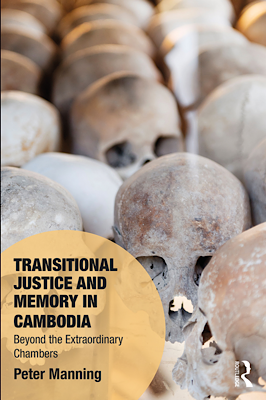

A central purpose of sites of memory devoted to the genocide is to put the full horrors of the past on display. Showcasing the violence and brutality of the past offers a veneer of humanitarian legitimacy to the Cambodian regime in the present. One of the preferred means of shocking visitors at these sites of memory is to put human remains on display. While this is completely at odds with Buddhist practices which call for the prompt cremation of the dead, especially with victims of violent deaths, great pains have been taken by government authorities to unearth and amass the bones of the supposed genocide victims and to place them on display at Buddhist stupas around the country. The killing fields of Choeung Ek, the nation’s principal memorial site just outside of Phnom Penh, includes a memorial stupa built in 1988 with over 8000 skulls on display behind glass panels.

Putting the bones of anonymous victims on display, similar to the tomb of the unknown soldier, is a means of nationalizalizing the dead. Similarly, provincial memorials to the genocide often neglect local histories and feature a standardized, national treatment of the genocide. This is certainly the case with Wat Thmey. Wat Thmey is one of dozen memorials built around the country in the 1980s intended to convey what Peter Manning describes as a “national account of loss and salvation from the Khmer Rouge.”

Since their construction in the 1980s, provincial memorial sites have also served as the locus of state-led commemorations. One of the most unusual commemorative events that began in 1983 but continues today is the “Day of Remembrance.” Originally called the Day of Maintaining Anger, the commemoration features a reenactment of the crimes of the Khmer Rouge. Sometimes elaborately staged with students dressed in black Khmer Rouge garb, the reenactors perform the gruesome murders of the past sometimes at sites like Choeung Ek where thousands of these killings actually took place. The reenactment, which concludes with the defeat of the Khmer Rouge and the end of the violence, continues to bolster the legitimacy of the current regime.

Is there a way to do justice to the memory of the genocide in Cambodia? Pete Manning reminds us that we need to be cognizant of the assumptions built into transitional justice institutions such as the ECCC. Claims to help countries heal from past traumatic events are rooted in western scientific notions that may justify invention but often have little relation to how real people relate to the past. Moreover, the supposedly beneficial and politically unbiased claims of transitional justice often mask how sponsor nations may be complicit in the very same crimes that they now adjudicate.

Many Cambodians, Manning stresses, paid little attention to the proceedings of the ECCC which had no real impact on their everyday lives. More significant, Manning argues, is the work of NGOs like DC-Cam and TPO. Despite their need to work within the political realities of Cambodia, these citizen initiates have worked toward meaningful and lasting changes. DC-Cam has evolved far beyond its original mission of collecting and preserving evidence of Khmer Rouge crimes. Under its charismatic leader Youk Chhang, DC-Cam has helped incorporate the story of Democratic Kampuchea into Cambodian school textbooks. TPO’s outreach work has included efforts to bridge the generational divide between those who lived through the horrors of the Khmer Rouge in the 1970s and younger generations of Cambodians who may have sincere doubts about the veracity of this past. Often operating in the shadows of more prominent institutions like the ECCC, NGOs like DC-Cam and TPO are laying claims to the past in ways that truly contribute to the wellbeing of Cambodians.

Peter Manning

Peter Manning is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Social & Policy Sciences at the University of Bath. He is the author of Transitional Justice and Memory in Cambodia: Beyond the Extraordinary Chambers