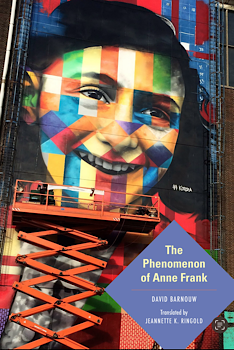

How can we understand the extraordinary scope and magnitude of global fame and notoriety achieved by Anne Frank? The Anne Frank diary has been translated into scores of languages and sold over twenty million copies. It has inspired countless books, movies and documentaries. The Anne Frank House in Amsterdam has become a major tourist destination attracting over 1.2 million tourists in 2019. Dutch historian David Barnouw, world renowned Anne Frank specialist, explains the enduring memory of Anne Frank in his book, The Phenomenon of Anne Frank.

The success of the diary of Anne Frank was an unlikely story. There were many diaries written during the war. In fact, the Dutch government in exile broadcast a radio address from London on March 28, 1944, encouraging Dutch citizens to record their experiences living under occupation. Otto Frank, the family’s sole survivor of the Holocaust, never set out to publish his daughter’s diary. He produced an original typescript in German which he sent to his mother and was subsequently lost. After repeated requests from friends to explain what life was like in hiding he decided to produce a second typescript to tell the story. The second typescript was a combination of Anne’s original diary covering her last months in hiding and her rewrite that she produced with dreams of becoming a novelist after listening to the Dutch government in exile’s radio address from London.

Otto was encouraged by his friends to submit the diary for publication. Despite initial rejections, he reached for an acquaintance in the publishing world who in turn passed the diary to others, one of whom published a flattering article which finally drew the attention of publishers. Beyond his persistence, when the progressive publishing house Contact agreed to take a chance on the diary, Otto demonstrated a considerable degree of flexibility with editorial requests. As the Calvinist Netherlands was quite conservative at the time, Otto agreed to remove a number of passages that were deemed too sensual or explicit for readers at the time. Of the twenty-six proposed deletions, David Barnouw notes, Otto agreed to sixteen. While flexible on editorial decisions, Otto changed the contract so that he kept future translation, stage and film rights—a decision that would be key to the eventual success of the diary.

First published in 1947, Het Achterhuis. Diary Entries from June 12, 1942—August 1, 1944, was unusual in that it went through several print runs, first in 1949 then again in 1950 and 1953 and generally received positive reviews. Not satisfied with only a Dutch publication, Otto found a German translator. Attuned to the sensitivities of a German audience, Otto agreed to the omission of a number of anti-German passages that might cause offense—although David Barnouw notes that Otto latter tried to blame the German publisher for these changes. The willingness to compromise on the content of the Diary in order to reach the widest possible audience, was undoubtedly central to the success of the book. In 1950 the book was published in German with the title “Das Tagebuch der Anne Frank.”

By 1950 the Diary was published in France and Germany and in 1952 an English language edition was released in the United States and Great Britain. Despite these three translations and favorable reviews the Diary was far from an international sensation. Print runs remained modest. The turning point seemed to come with a glowing review in June 1952 by Meyer Levin on the front page of the prestigious New York Times Book Review. After the review print runs grew from 15,000 to 40,000 copies. A number of newspapers, Barnouw notes, were interested in publishing the Diary in serial form.

Nevertheless, it’s a fact that the play, more than the book, has determined the image of Anne Frank for the greater public: a happy, lively girl who falls in love and sometimes has profound thoughts. Anne has become the symbol of universal human suffering rather than “the voice of six million vanished [Jewish] souls.” David Barnouw, The Phenomenon of Anne Frank.

Ironically, one of the chief proponents of the play, the American novelist Meyer Levin (1906-1981), ended up in court against Otto Frank. Meyer Levin convinced Otto Frank that he was responsible for the success of the book and to give him the opportunity to write the play. But after each of Levin’s choices for producers rejected his play, Otto reached for the law firm of Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton, and Garrison to settle the matter. A contract was written in which Levin agreed to accept his fate if fourteen named producers refused the play. Thinking he was finally rid of Levin when this happened, Levin ended up suing Frank for fraud and breach of contract in 1956 before the Supreme Court of New York. Levin claimed that Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett, who produced the play, used his work without permission. Moreover, Levin wanted the right to produce his own version of the play. In the end, in 1959 Levin agreed to a settlement for $15,000 and relinquished all rights to the play to Otto Frank.

Levin’s main bone of contention was that his version of the play was rejected because it was too Jewish. It is true that Otto Frank disliked the Zionist and and religious elements that were a prominent feature of Levin’s play. Otto’s own background was assimilationist and his daughter’s Diary had few Jewish or Zionist traces. Rather than planning to go to Palestine after the war like her sister Margot, Anne dreamed of spending a year in Paris and London studying art history and language. Levin was critical of the Goodrich and Hackett play for stripping the Jewishness from the Dairy without acknowledging his own distortion of Anne’s person.

It was the stage adaptation by Frances Goodrich (1890-1984) and Albert Hackett (1900-1995) that catapulted Anne Frank to international notoriety. The play opened in 1955 and went on to over 700 performances. It won a Tony, Pulitzer Prize for drama and the New York Critics’ Critics Circle Award for Best Play. Seventeen-year-old Susan Strasburg, who opened as Anne in her debut performance, became the youngest lead actress on Broadway. It was the play, David Barnouw stresses, that ultimately shaped the image of Anne Frank for a global audience.

Central to the success of the play was the transformation of Anne Frank into an American teenager. “Anne Frank was abducted by American playwrights,” David Barnouw jokes, “and sent back as a joyful American teenager.” There are hardly any signs in the play, Barnouw remarks, that the family is in hiding. Anne is like any other teenage girl who had disagreements with her mother. And when the play concludes, no mention is made of Anne’s death in 1945 at the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. Instead, the play finishes on a feel-good note with Anne exclaiming that “I still believe, in spite of everything, in the goodness of people.”

After the death of Otto Frank in 1980 who would preside over the legacy of Anne Frank became a subject of contention. Three poles of authority took shape, the Anne Frank Foundation in Basel, the Anne Frank Stichting or Foundation in Amsterdam and the Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies (NIOD), headquartered in Amsterdam. Because he had relatives in Switzerland Otto Frank moved to Basel where he founded the Anne Frank Foundation in 1963. As profits from the Diary, plays and movies based on the book began to soar it was the Anne Frank Foundation that benefited most because Otto Frank gave it the copyright. Until the 1990s, Barnouw notes, the Anne Frank Foundation collected money and gave it to various charitable causes. Most people had never heard about it and there is no public record of the receipts generated by the Diary.

The Anne Frank Foundation in Amsterdam was established in 1957 and manages the museum at 263 Prinsengrach in Amsterdam, known as the Anne Frank House. Preserved, in part, in conjunction with a larger effort to safeguard the architectural integrity of Amsterdam in the post-war years, the Anne Frank House became a destination for largely American tourists. Only over the past thirty years, notes Barnouw, have the Dutch taken an interest in the museum/building and come to see it as an integral part of their national patrimony. During Otto Frank’s life the future of the Anne Frank House was far from assured. Moreover, the activism of the Anne Frank Stichting during the 1960s and 1970s in favor of a variety of issues didn’t ingratiate it with Otto Frank, himself a former Prussian officer in the German army during World War I whose views were somewhat conservative.

Unsure about the future of the Anne Frank Stichting and at odds with its politics, Otto Frank decided to bequeath ownership of the Diary to the NIOD where it would have a safe and secure home. The Anne Foundations in Basel and Amsterdam have always had a contentious relationship. Although it benefited from the royalties generated by the Diary, the Foundation in Basel did little to help with the cost of the extensive renovations to the Secret Annex at the end of the twentieth century. On numerous occasions disagreements over film projects, ownership of Frank family documents, and even the international rights to the Anne Frank brand had ended up in court. While the NIOD reached an agreement for the Diary to remain on permanent display at the Anne Frank House, the struggle over the legacy of Anne Frank between the two foundations has yet to be resolved.

David Barnouw

David Barnouw has been researcher and spokesperson at NIOD, the Dutch Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies. He is active as a writer and lecturer and one of the two editors of The Diaries of Anne Frank, the Critical Edition. He is a world renowned specialist on Anne Frank and the author of The Phenomenon of Anne Frank.