In June 2004 a thirty-member multiracial task force known as the Philadelphia Coalition stood on the stage of the Neshoba County Coliseum before a crowd of a thousand people. What was unique about the Philadelphia Coalition wasn’t that whites finally joined Neshoba County blacks in commemorating the lives and deaths of three young civil rights workers murdered outside Philadelphia, Mississippi in June 1964. This had already happened with the twenty-fifth anniversary commemoration in 1989. What made the Philadelphia Coalition different was that their work didn’t end with the commemoration. The Philadelphia Coalition helped reopen the case and finally brought to justice Edgar Ray Killan, the leader of the local Klansmen responsible for the murders. Determined to change the hearts and minds of fellow Mississippians, the Philadelphia Coalition provided the impetus for a bill that made civil rights education mandatory across the state and for the creation of a South African style Truth and Reconciliation Commission to look at racially motivated crimes in the state’s past. How commemorations can become something larger, something transformative, is the focus of Furman University sociologist Claire Whitlinger’s book, Between Remembrance and Repair: Commemorating Racial Violence in Philadelphia, Mississippi.

James Chaney, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman became targets of local Klansmen for their participation in the 1964 Freedom Summer. Most well-known for its effort to register black voters, participants in the Freedom Summer also set up schools to teach literacy and civics and to challenge the all-white stranglehold on Mississippi’s Democratic Party. What no one ever expected was that within a week after the start of the program, Cheney, Schwerner and Goodman would vanish. After a month-long intensive investigation, FBI agents finally discovered the bodies in a makeshift grave. However, the state refused to press charges for murder against the 18 men implicated in the crime. Several were finally convicted on lesser federal charges, but none spent more than a few years in jail and Edgar Ray Killen was never convicted

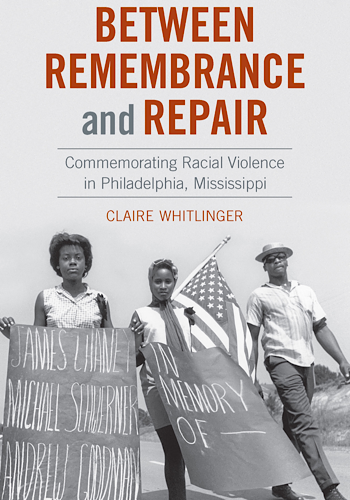

In the scholarship the twenty-five-year period that followed the murder until the first large commemoration in 1989 became known as the long silence. This was because the story of the murders was never taught in local schools and never discussed by local officials. A whole generation grew up knowing next to nothing about this past. But Neshoba County’s black community never forgot. Just ten days after the murder they organized a commemorative service on the charred ruins of the fire-bombed Mt. Zion United Methodist Church, which Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner had investigated just prior to their murders. Every year, mostly African Americans gathered at Mt. Zion for a memorial service and often a march that ran through the town. These were the memory keepers who kept the memory of Philadelphia’s past alive during the decades it was suppressed by the dominant white community.

As white residents largely avoided discussing what they often referred to as “the troubles” of 1964 in the decades following the murders, black churches erected monuments, hosted memorial services, and nourished protesters who marched in memory of the three civil rights activists. Philadelphia, then, was not silent about the murders. Rather, its long history of commemoration has been silenced by historical reconstructions that conflate the city’s history with the history of its white citizenry, a phenomenon that has been common throughout much of southern historiography. Claire Whitlinger, Between Remembrance and Repair: Commemorating Racial Violence in Philadelphia, Mississippi.

What changed everything was director Alan Parker’s 1988 Oscar Award winning depiction of the murders, Mississippi Burning. Although criticized for a number of historical inaccuracies, the film became a bombshell for Neshoba County whites, many of whom were still oblivious about the town’s past. Moreover, the film put the small town of Philadelphia in the national and international spotlight. It was clear, Claire Whitlinger remarks, that people were going to come to Philadelphia in large numbers for the twenty fifth anniversary of the murders in 1989. Nashob county whites either had to continue to let others define their community or they could write the next chapter themselves. This was their opportunity to show the world that they were no longer the heart of darkness as long depicted by the press.

The 1989 commemoration was significant for a number of reasons. Prominent state and local officials spoke at the event. Secretary of State Dick Molpus, a native of Philadelphia, gave a formal apology. This was the first time whites and blacks had come together to publicly address the wrongs of the town’s past. But for all of its novelty and significance, Claire Whitlinger argues that the 1989 commemoration was an event without a second act. After the commemoration, the community returned to its normal state of affairs. There was no measurable impact on the community or its organizers. In this respect, it was much like most commemorations where the planning and staging of the event is the sole aim, objective and measure of success.

What was different about the 2004 commemoration was that the organizers articulated the goal of justice while planning the event. Commemorating the lives and deaths of the slain civil rights workers wasn’t enough. They were determined to do everything possible to reopen the case and finally bring to justice Edgar Ray Killen. What was different about the 2004 commemoration was that the organizers didn’t disband and return to their normal lives. They continued to work together not only to pressure local authorities to reopen the murder case but also to pass a bill to include civil rights education in schools across Mississippi and to create a commission to investigate racially motivated crimes in the state’s past.

How this happened, Claire Whitlinger came to realize, had much to do with the dynamics of intergroup contact. Under particular conditions, explained by Gordon Allport in his 1954 book, The Nature of Prejudice, otherwise divided groups can forge a shared identity and larger sense of purpose. Allport’s three conditions include 1) equal status within the group allowing for everyone to fully participate, 2) cooperation towards a larger goal that requires everyone to work together, and 3) support by local authorities. Claire adds a final condition from Thomas Pettigrew, friendship potential, or the possibility through informal, intimate contact to form bonds of friendship. The 2004 commemoration met all of these conditions allowing the multiracial task to see themselves as the Philadelphia Coalition, a closely knit group with a larger purpose than just organizing an event.

Carefully coordinated and well-moderated Intergroup contact, Claire explains, can function like cognitive behavior therapy. Exposure has the potential to reduce fears and anxieties while increasing levels of comfort and certainty. Intergroup contact allows members of diametrically opposed groups to overcome their preconceptions and prejudices and to build trust and empathy. Self-disclosure, or revealing personal information, is a key part of the process of breaking down barriers. Storytelling is a common vehicle for self-disclosure and one which featured prominently in the experience of the Philadelphia Coalition. Through the skillful mediation of Susan Glisson, the recently appointed head of the newly created William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation at the University of Mississippi, members of the Philadelphia Coalition shared stories about their lives for the first time across the color divide.

The results of this intergroup contact work could not have been more consequential. Early on the Philadelphia Coalition reached a consensus that justice had to be done. Edgar Ray Killen, the mastermind of the Mississippi Burning murder continued to live a normal life in Neshoba County, decades after taking the lives of Cheney, Goodman and Schwerner. The Philadelphia Coalition helped reopen the case and brought justice to Killen, who in 2006, died in prison at the age of 92. Working together with the William Winter Institute, the Philadelphia Coalition helped with the passing of Mississippi Senate Bill 2718, mandating the inclusion of civil rights education across the state. Finally, the Philadelphia Coalition was instrumental in the creation of a South African style Truth and Reconciliation Commission, called the Mississippi Truth Commission. Originally envisioned as a body of experts who would investigate the history of racially motivated crimes in Mississippi, it ultimately evolved into an oral history project.

Is the work of the Philadelphia Coalition replicable elsewhere? The experience of what happened in Neshoba County is not a model that can easily be packaged and reused. This said, the ability of members of a community long divided along racial lines to come together, to overcome fears and prejudices, and to achieve lasting accomplishments in the realms of justice and education does offer hope for seemingly intractable problems in other parts of the country or globe. The key, Claire Whitlinger stresses, is the process. The Philadelphia Coalition began by getting to know each other, sharing stories, building trust and empathy. In the end, this made all the difference.*

*I would like to thank Jean-Baptiste Chuat for allowing me to use his photo on the landing page for this episode.

Claire Whitinger

Claire Whitlinger is Associate Professor of Sociology, Founder and Co-Director of the Intergroup Dialogue Program at Furman University in Greenville, South Carolina. She is the author of Between Remembrance and Repair: Commemorating Racial Violence in Philadelphia, Mississippi (UNC Press, 2020)