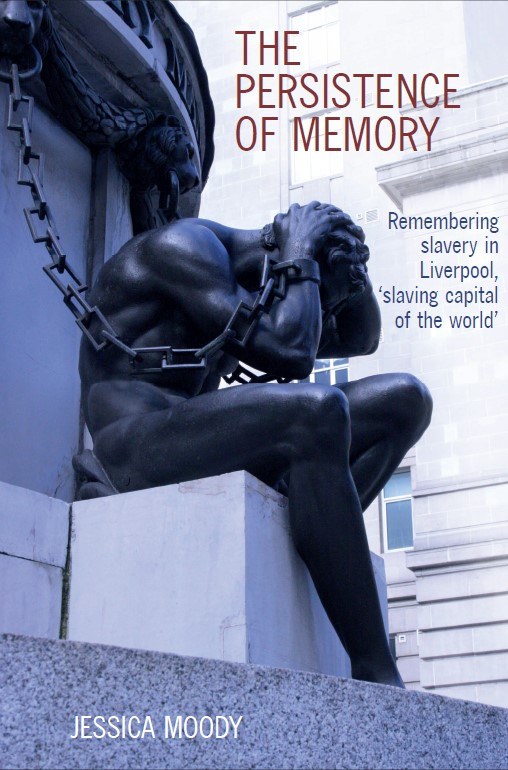

Liverpool was the world’s leading slave trading port in the eighteenth century. How has the memory of the slave trade persisted in Liverpool over the past two hundred years? Jessica Moody, lecturer in public history at the University of Bristol and author of The Persistence of Memory: Remembering slavery in Liverpool, ‘slaving capital of the world,’ argues that memory of the slave trade has persisted through the language of public debates that intermittently surface about the city’s past. It has persisted through the hostility aimed at and the memory work of Liverpool born blacks, the country’s oldest black community. It has persisted in celebrations of the city’s founding that coincide with the anniversary of the abolition of slavery. It has persisted through the stories about the places around the city where slaves may have been bought, sold, chained, and held.

The magnitude of Liverpool’s role in the slave trade and the impact of this commerce on the city cannot be overstated. In the span of just about fifty years, during the last half of the eighteenth century, Liverpool ships transported over 1.4 million Africans to the Americas. In roughly half a century Liverpool ships carried ten percent of all the Africans transported during entire four hundred year history of the transatlantic slave trade. The slave trade made Liverpool a magnet for immigrants from Scotland, Wales, and surrounding areas. The city’s population increased ten fold over the course of the eighteen century. By the end of the eighteen century, nearly one in eight Liverpool families was dependent on the slave trade. Beyond tradesmen, craftsmen, and sailors, the slave trade drove the rise of Liverpool’s banking and insurance industry. The sons of Liverpool slave merchants went on to Oxford and Cambridge, the country’s most prestigious universities.

While there was tremendous fear about the potential economic repercussions of the end of the slave trade, the city was able to survive the economic shock. One of the ways in which the memory of the slave trade persists in public discourse, Jessica notes, is the notion that if Liverpool overcame abolition then the slave trade could never have really mattered to Liverpool. Diminishing the significance of the slave trade was also a way for Liverpool to get in line with the new more progressive abolitionist narrative of British identity that took shape in the nineteenth century. “It would be accurate to say that what Britain has remembered is not slavery, but abolition,” Jessica notes. “The country achieved this through the celebration of national heroes—William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson, Fowell Buxton and other figures.” The commemoration of particular anniversaries also played a part in the construction of this abolitionist narrative. “In particular, the centenary of the Emancipation Act in 1933 and 1934 and, of course, the Abolition Acts as well.” On the national level, Jessica stresses, “Britain will talk far more in public discourse and in public memory about its own history of abolition, celebrating the idea that it abolished its own slave trade, without really mentioning the previous four hundred years.” Remembering abolition and forgetting the slave trade in the nineteenth century, Jessica adds, “was also a way of justifying imperial expansion into Africa to try and abolish the East African slave trade, the Muslim and Arab trades. It became a usable past.”

As a millennial, Jessica considers her own exposure to the history of the slave trade and the British Empire through the British education system as being very typical of her generation. “I didn’t learn about the transatlantic slave trade, transatlantic slavery or anything about the British Empire in school.” Only in places that had a direct connection to this history, like Bristol or Liverpool, Jessica adds, was this history sometimes added to local studies curriculum. “I knew nothing about this. I thought that slavery was something that happened in America, in the United States. Or something that was to do with Africa. I did not know and did not understand how central Europe was and that Britain had played such a huge part.” Only after moving to Liverpool in 2003 for her university studies did Jessica discover this past. While taking an open-top red bus tour around the city with her grandparents and stopping at the Albert Dock, Jessica heard a recorded voice describe how Liverpool traded products with the entire world. In a matter-of-fact tone, the recording added that Liverpool was also “number one for slavery.” “I thought that was a very strange way of phrasing such a huge involvement with such a difficult history. I think it was from there that I learned about it and looked more into it.” With permanent museum exhibitions devoted to this history since 1994, Jessica notes that Liverpool was one of the few places in Britain, at the time, where you could learn about Britain and slavery.

In her research on how Liverpool remembers the slave trade Jessica tried to look at a wide variety of public sources. These sources included Liverpool’s first written histories and guidebooks as well as a number of leaflets and newsletters published across the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. “What I found,” Jessica remarks, “were some really regularly repeated narrative structures.” These narratives are like deeply grooved ways of thinking about the city that persist across the centuries. One the most prominent recurring narratives is the idea that Liverpool won at the slave trade. “This goes back to the red bus tour I took with my grandparents. You had historians in the nineteenth through to the twenty-first century saying Liverpool beat Bristol and London out of the slave trade.”

While the idea that Liverpool succeeded in the slave trade has had long staying power, there are also narratives in which Liverpool is ridiculed for excelling at such a despicable commerce. “One of the more interesting historical narratives that repeats across different media,” Jessica adds, “is this idea of dissonance.” Jessica explains that “by the early twentieth century, slavery and the slave trade is seen as both the glory and the shame of Liverpool. It’s seen as something that was glorious, it was something to take pride in, and is now seen as shameful, as morally corrupt, as something that is anti what British national identity is. Because by this point Britain has an anti-slavery empire. That becomes part of the raison d’être for pushing further into Africa, for taking control of different peoples, for apparently their own good.”

Another enduring subject of debate centers on the actual presence of slaves on Liverpool soil. Whether actual slaves lived in the city, whether they were bought and sold in Liverpool, Jessica notes, “becomes a real focus of debate.” “I guess it’s because it brings it home in a way that talking about ships and triangular trade and goods doesn’t really. Because those are all, sort of, inanimate things. Whereas people, that’s the human aspect. That’s the real trauma of this history.”

What makes it impossible to suppress the memory of the slave trade in Liverpool is the city’s black community. Liverpool has the country’s oldest black population stretching back at least two hundred years. Liverpool born blacks, as members of this community call themselves, have a distinct identity shaped by a long history of racially motivated violence and discriminatory policies. It was the mobilization of this community, both as memory actors and through clashes with city authorities, that helped foster a greater degree of awareness and public recognition of the history of the slave trade in Liverpool.

In contrast to most blacks in Britain with roots in the Caribbean, Liverpool’s black community comes primarily from West Africa. Stories like that of the Empire Windrush, the ship which brought many of the earliest Jamaican blacks to Britain in 1948, are well known. “However, Liverpool has black families, of African and Caribbean descent who can trace their family trees back to the eighteenth century.” Some have a direct connection to the slave trade but most are tied to peripheral activities. “West African elites,” Jessica explains, “sent their children to learn about the trade. Then, into the nineteenth century, you get a lot of men in particular, working on the steamship lines from West Africa to Liverpool. So you have this long, historical black presence and one that is English, that has families, that marry, that settle in the city, and have longevity. And for a long time they were treated terribly. There was a lot of institutionalized, systemic racism through employment, education, housing, you name it, and at the hands of the city authorities and universities as well the museums, cultural organizations too.”

While narratives about the city’s past might celebrate how Liverpool beat Bristol and London out of the slave trade, Jessica notes, there is a “huge dissonance between the stories that aren’t being told, of course, in relation to people of African descent.” “What’s also really important,” Jessica stresses, “is that people of African descent in the city are also active agents in memory work as well.” Here Jessica comments on the example of Eric Scott Lynch who gave slavery walking tours of the city starting in the 1970s until late into his life. A self-educated guide, Lynch informed guest on his walking tours about the connection between Liverpool’s buildings and the history of empire and slavery. Institutions such as the Charles Wootton College, named after a black sailor murdered in race riots in Liverpool in 1919, ran a black studies course and history workshops targeting minority populations.

“One of the most poignant ways the black community led the way in resisting these problematic narratives,” Jessica remarks “was through the kinds of resistance we see in the 1980s.” Riots erupted in a number of British inner cities in the early 1980s. The 1981 riots in Toxteth, Liverpool were the largest. “What we see after this is a sort of reaction by city authorities to try and make some moves in the right direction. So you have reports that are written. A report called ‘Loosen the Shackles,’” Jessica remarks, is “quite ominously titled in ways that connect it metaphorically to Liverpool and slavery. And it’s also after that that you start to get the museums introducing different displays.”

Beyond it’s black community what makes Liverpool unique is its dual anniversaries. Liverpool’s founding date is 1207 when a letter patent was granted by King John making Liverpool a free borough. Because the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act was passed in 1807, when city authorities decide to celebrate the Liverpool’s 700th anniversary in 1907, they also had to contend with the 100th anniversary of the abolition of the slave trade. This was a time of tremendous growth and prosperity, a time when some of Liverpool’s most prominent buildings were erected such as the Three Graces—the Royal Liver Building, the Cunard Building, and the Port of Liverpool Building. City authorities wanted to celebrate Liverpool’s birthday to foster a greater degree of civic pride and to challenge critics who claimed that Liverpool had no culture, was just a commercial town, and its people were ignorant of its history.

Emulating the commemorative practices of other cities, Liverpool authorities decided to showcase a huge historical pageant with a parade of horse drawn cars. Because each car, in chronological order, would feature different themes, events, and people in the city’s history, it was impossible to leave out the slave trade. “So they end up having to have a car that celebrates the slave trade in this procession that has allegorical figures. There’s a female figure in the middle epitomizing wealth, there are people playing slave traders, like Hugh Crow, and then you have actual African people, black African people in this procession, taking on the parts of slaves, and there are chains all around this car.” What resulted, Jessica notes, was an “awkward juxtaposition of a difficult and horrific history in a pantomime” which celebrated the past while downplaying and sanitizing it. Reflecting the imperial paternalism of the day, Jessica remarks how the slave car was followed by the philanthropy car. “So you have the slave trade car, then you have the philanthropy car. And it’s almost like this is an atonement. This one makes up for the other. And it’s celebrating these philanthropic figures of Liverpool who made their money in slavery as well.”

Then, in 1957, Liverpool celebrated its 750th anniversary. This is not as grandiose as 1907, because of the budget strapped reality of Britain after World War II, but there are exhibitions, leaflets, and even a five hundred page commemorative history of Liverpool given to dignitaries invited to attend the event. “In this written history, the author at the time, George Chandler, severely downplayed Liverpool’s role in the slave trade. There was only a page on it.” When we move on to 2007 and Liverpool’s 800th birthday, even less attention is given to the slave trade. “It’s the year before Liverpool is given the capital of culture title from Europe and it’s the bicentennial of the abolition of slavery. It was a time when events were taking place up and down the country, not just at port cities but in landlocked places, archives, community centers, theaters and museums. Lots of things were going on so it wasn’t just Liverpool and Bristol. What happens in that year, is that compared to 1907 and 1957, slavery is talked about the least in Liverpool’s birthday celebrations. Perhaps because it’s been compartmentalized into the bicentennial.”

As Liverpool celebrates its dual anniversaries we also see the evolution of its leading citizen, William Roscoe. “Williams Roscoe, I think, is an interesting barometer of what’s going on in public memory of slavery in Liverpool at different points in time. He eventually becomes a hero of the city and is celebrated for lots of different reasons.” Jessica explains that when Liverpool is criticized for its perceived lack of culture Roscoe’s achievements as a poet and patron of the arts are spotlighted. But when Roscoe died in 1831, and his friends and supporters wanted to remember his role in the abolition movement, city authorities were cold to the idea. “They don’t want anything that references African people or chains.” Much later, in the twentieth century, Jessica notes, Roscoe is reimagined. “This happens a lot, I think, with civic heroes. These figures who in relation to place and identity are used and reused, invented and reinvented, overtime for what they can celebrate in that particular given moment. What people feel they need in that given moment.” So when Britain is commemorating the centenary of the Abolition Acts in 1933 and 1934, Roscoe is reinvented as an anti-slavery hero. “And then you find he’s often used in debates as sort of counter argument to Liverpool’s intense involvement in slavery and the slave trade; but we had William Roscoe, and William Roscoe voted to abolish this trade.”

Whether actual slaves lived in the city, whether they were bought and sold in Liverpool, Jessica notes, “becomes a real focus of debate.” “I guess it’s because it brings it home in a way that talking about ships and triangular trade and goods doesn’t really. Because those are all, sort of, inanimate things. Whereas people, that’s the human aspect. That’s the real trauma of this history.”

Museums that addressed the history of the slave trade in Britain traditionally did so by celebrating the biographies of the leading abolitionists. The William Wilberforce House in Hull, the Cowper and Newton Museum in Buckinghamshire, and the Wisbech Museum in Cambridgeshire, tell the story of the architects of the anti-slavery movement. It wasn’t until the 1990s that we see the creation of the first public institutions devoted to the history of the transatlantic slave trade. The establishment of the Transatlantic Slavery Gallery in Liverpool in 1994, followed by the International Slavery Museum in 2007, mark a shift in national public memory from abolition to slavery. The development of these museums, however, was fraught with challenges and difficulties. In particular, questions about who should be involved in the museum planning process, whose story should be told, had the potential to deepen racial divisions and to reinforce an older abolitionist national identity.

While Liverpool has had more permanent museums devoted to the history of the slavery than anywhere else in Britain, Jessica remarks that “we shouldn’t see museums as a solution to a problem. We shouldn’t say that we fixed forgetting or we fixed Liverpool’s public memory of slavery.” “British museums didn’t have much experience with histories implicating minority communities,” Jessica notes, “so it was a learning process understanding how to include them in the planning.” With the Transatlantic Slavery Gallery there were intense conversations about how to use language that humanized and broke with the tradition of commodifying Africans. As part of this desire to give Africans more agency the decision was made to include displays on Africa before slavery. But despite these efforts museums had a long association with white dominated power structures and collections built on a history of imperialism which engendered sentiments of distrust among blacks.

One important source of tension with the black community and the International Slavery Musuem is the treatment of contemporary forms of slavery. “Things like human trafficking, sex trafficking, wage slavery, bonded labor, the kinds of things that charities like Anti-Slavery International, who also have historic roots through British abolitionism, are tackling. Some people of African descent in the city don’t think those things are the same.” A central concern is that the focus on these contemporary issues might divert attention from the history and direct legacies of transatlantic slavery, “namely anti-black racism.” “So you are not talking about that as much as you are talking about sweatshops in Indonesia. And that’s seen as, in some cases, maybe a deflection, maybe an expression of neo-abolitionism. There is an idea that white saviors are coming into this again.”

In 1999 Liverpool became the first city in England to issue an official apology for its role in the slave trade. It was part of a global wave of apologies which some historians have argued were part of an international memory boom triggered by the fiftieth anniversary of the end of World War II and the commemoration of the Holocaust. Jessica argues that apologies need to be understood as speech acts. They are performed by particular actors, targeting specific audiences with carefully selected words and clearly defined objectives. It was in many respects the muddled nature of the apology issued by Liverpool’s City Council that caused it to fall flat.

“As a speech act,” Jessica explains, “you need to know who the apology is coming from, who it is going to, and what the actual content of that apology is.” She notes that Liverpool’s apology was criticized for being rushed, driven by a perceived desire to get it done before the end of the millennium. It was seen as possibly being driven by the political careers of those involved. Moreover it wasn’t exactly clear who was issuing the apology. “The way it was performed made it seem like it was coming from the city council as the leading authoritative body of the city but the language read as a collective we that was more about the whole city.” Moreover, for an apology to work, Jessica wondered, “don’t they have to accept it? I don’t think this was something that was accepted. A lot of people of African descent were concerned by how it had taken place. Little consultation, little sense of what happens next. Is an apology on its own enough or should there be actions that go with it? A lot of people didn’t see any actions that came out of it.”

While Liverpool lacks a memorial to enslaved Africans what it does have is a rich memoryscape. These are spaces around the city with layers of stories linking them to enslaved African people. “Whether they are true or not, what’s important about them is that they persist and people keep telling them. This idea that there were enslaved African people who were bought and sold in the city, who lived, married, had children, died here. This idea of people being physically present in the city. Enslaved African people being the human part of this history is really poignant.”

Many of the stories about enslaved people in Liverpool center on areas along the River Mercey. In the eighteenth century the River Mercey came up to a road called Goree. Gorée is an island off Senegal which functioned as a transit point—although contested by some historians—for large numbers of slaves from West Africa. The Maison d’Esclaves (House of Slaves), a UNESCO world heritage site, is located on Gorée. The use of the name Goree for a part of Liverpool long associated with stories about slaves only reinforces this connection.

The area surrounding the Goree warehouses, built in the late eighteen-century and finally demolished in the mid-twentieth century, is layered with decades of stories about enslaved Africans. Now vanished physical features like metal rings have long been connected to stories about enslaved Africans being chained to them. There are stories that Africans were sold in a nearby square known as Goree Piazza. Stories persist about tunnels and special holding rooms under building where slaves were held. “Again this isn’t that it necessarily happened,” Jessica comments, “but people are connecting iconography in their built environment and making connections to the human story. So you might see a ring by a pillar and think someone could have been chained to that.” When the Goree warehouses were finally destroyed Jessica finds it “wonderfully ironic” that an office block was built on the same location and named Wilberforce House. “So you get this displacement of a difficult memory of slavery with a more comforting memory or narrative of abolition in that place.”

Memories of our darkest chapters may be exorcized from official memory but they still persist in public memory. In the case of Liverpool, memories of the slave trade persist in the form of narratives of pride and shame about the city’s past. They persist through debates about whether slaves were bought or sold, lived or died in Liverpool. They persist through sites of unofficial memory where stories about the presence of slaves stretch across time.

Motivated in large part by the struggle of Liverpool born blacks for justice and recognition, city authorities have made efforts to grapple with the history of the slave trade. From the opening of permanent museum displays to the issuing of an official apology, meaningful steps have been taken to start the process of confronting the past. This is an important departure for a country that has until now sought solace in the narrative of abolition. But as evidenced by the muddled nature of the apology and the neo-abolitionist message of the International Slavery Musuem, this is a process fraught with challenges and difficulties with much more work to be done.

Jessica Moody

Jessica Moody is a lecturer in public history at the University of Bristol. She is the author of The Persistence of Memory: Remembering slavery in Liverpool, ‘slaving capital of the world’