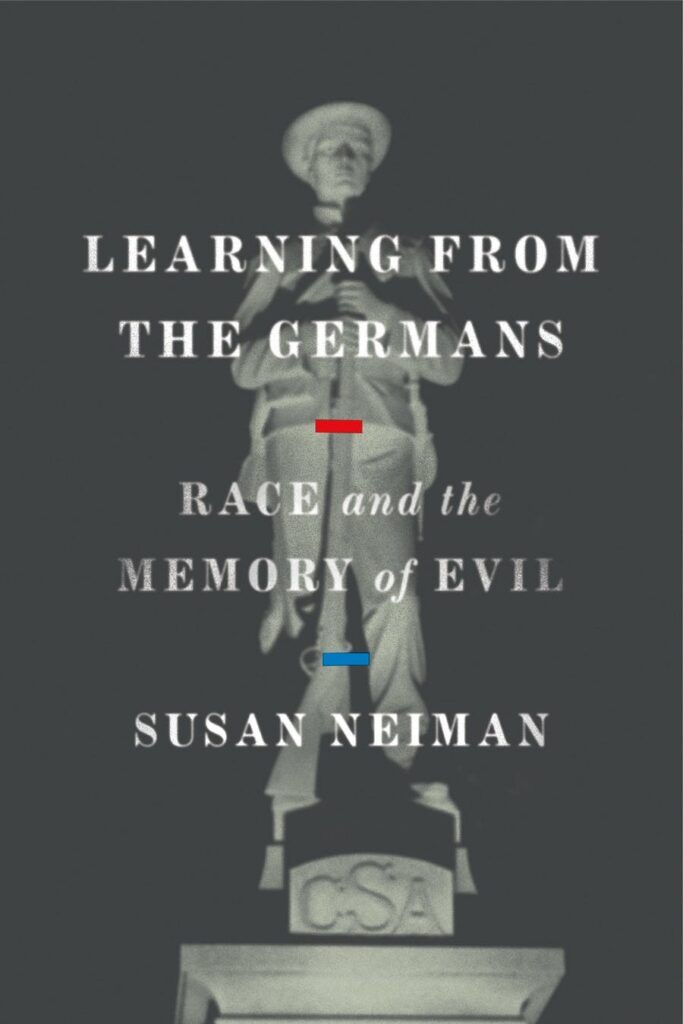

How did Germany go from being an international pariah at the end of World War II to a leader of the European Union and one of the most trusted nations on the planet? In Learning from the Germans: Race and the Memory of Evil, Susan Neiman, director of the Einstein Forum in Berlin, argues that having the courage to confront the past did much to transform Germany’s image at home and abroad. In this debut episode of Realms of Memory, Susan Neiman explains how Germany was able to take up the challenge of addressing its darkest chapter and what other nations can learn from the Germans.

Any visitor to Berlin today will experience first hand the German willingness to face and atone for the nation’s past crimes. A glass dome, symbolizing a desire for transparency, now tops the Reichstag, the German parliament building. A Holocaust memorial takes up five acres of prime real estate at the very heart of the nation’s capital. Artist Gunter Demnig has embedded over 61,000 stolpersteine or stumbling stones, bronze pavers engraved with the names and deportation dates of the victims of the Holocaust, on the streets and in front of the homes where the victims once lived.

Susan asserts that there are three important lessons we can take from the Germans. The first lesson is that this willingness to confront the past takes a long time and will invariably meet with considerable pushback. Decades after the war most Germans continued to believe that they were the war’s greatest victims. A traveling exhibition organized by the Hamburg Institute for Social Research in the 1990s on how the Wehrmacht, the German military, was complicit in the crimes of the Nazi past, triggered a massive public outcry and a storm of media debate. Given that over 18 million men served in the Wehrmacht, most Germans had a father, grandfather or other family member implicated in this past. It far was more comforting to think the crimes of the Nazi regime were limited to special killing units like the SS and not ordinary Germans, especially loved ones. Although the role of the Wehrmacht in the brutal treatment of prisoners of war and populations in occupied territories is a subject that has been thoroughly documented by scholars, Susan points out that there is always a gap between academic scholarship and public awareness.

The second lesson lesson is that there is no one way of confronting the past, not even for the Germans. Germany was divided after the war into a democratic West Germany and a communist East Germany. Contrary to popular opinion, East Germans were actually far ahead of West Germany in addressing the Nazi past. Given that most of the leaders of East Germany were devoted communists, persecuted by the Nazis, and forced to flee to places like the Soviet Union during the war, it should come as no surprise that they were more committed to rooting out all vestiges of the previous regime. When it came to purging the civil service, putting former Nazis on trail, and transforming the education system, far more was done in East than in West Germany.

In West Germany, the vast majority of former Nazi educators and civil servants remained in their jobs well into the 1960s. The Nuremberg Trials were generally dismissed by Germans as victors’ justice and as the Cold War heated up American occupying forces became far more interested in fighting communists than hunting down former Nazis. One of the main differences between East and West Germany, Susan explains, is that efforts to address the Nazi past was a top down process in the East and a bottom up one in the West. Change was imposed from above in East Germany whereas it came from below in the West.

The third and perhaps most important lesson is that it is possible for nations to confront their darkest chapters and to come out the better for it. It may have taken the Germans decades but Germany is now a more trusted and respected nation and one of the most welcoming countries on the planet. When the Middle East erupted in violence with the rise of Isis, Germany welcomed over a million refugees within the span of a year—far more than any other country in Europe. With the fighting in Ukraine and the exodus of several million Ukrainians, Germany is once again poised to welcome unknown numbers of new refugees. Susan is convinced that if the Germans can confront their past and come out the better for it than so can any other nation.

Susan doesn’t believe there was a single turning point in West German history or that we can even credit generational change for transforming the mental landscape regarding the Nazi past. It was rather an array of civil society initiatives that gradually created pressure from below to acknowledge and make amends for past crimes. It was a slow process that began in the 1950s with church groups and intellectuals. The Wehrmacht Exhibition is one of the more prominent examples of this bottom up approach to memory in Germany.

Susan is quick to point out that working through the past is always an incomplete process and Germany still has more work to do. However, Germany is exceptional in one important respect. Most countries, Susan explains, would rather see themselves as heroes. When this isn’t possible they generally cast themselves as victims. While Germans do see themselves as victims of the Nazi past they recognize that others suffered far more than they did and it was Germany’s fault. Germans are exceptional precisely because they have found the courage to see themselves as perpetrators.

Having the courage to face and take responsibility for the past can deepen the bonds of trust and confidence both at home and abroad. If ever there was a time when this is most needed, it is now.

Beyond the difficulties, duration, and pushback, the most important lesson other nations can take from the Germans is the far reaching benefits of an honest and open accounting of the past. Having the courage to face and take responsibility for the past can deepen the bonds of trust and confidence both at home and abroad. If ever there was a time when this is most needed, it is now.

Susan Neiman

Susan Neiman is Director of the Einstein Forum in Berlin. Born in Atlanta, Georgia, Susan studied philosophy at Harvard and the Freie Universität, Berlin and was a professor of philosophy at Yale and Tel Aviv University. She is the author of Slow Fire: Jewish Notes from Berlin, The Unity of Reason: Rereading Kant, Evil in Modern Thought, Fremde sehen anders, Moral Clarity: A Guide for Grown-up Idealists, Why Grow Up?, Widerstand der Vernunft. Ein Manifest in postfaktischen Zeiten, and Learning from the Germans: Race and the Memory of Evil