With the Communist victory in China in 1949 nearly one million civil war refugees flooded into Taiwan—the largest out migration from China in the modern era. Dominic Meng-Hsuan Yang, author of The Great Exodus from China: Trauma, Memory, and Identity in Modern Taiwan, helps us understand the relationship between trauma and memory in new ways. He reveals how the memories of mainlander refugees changed over time and the therapeutic role they served. He sheds light on how mainlander refugees and their descendants used their memory work to lay claim to a new home in Taiwan. Perhaps most importantly, Dominic reveals how his own personal journey of understanding might offer the promise of reconciliation between long embattled communities who see the past in very different ways.

To properly understand the nature of the trauma experienced by mainlander refugees, Dominic argues that we need to break with the Western psychoanalytic tradition. This tradition frames trauma as a singular event that destabilizes the identity of the individual by leaving behind memories that are damaged, repressed or simply too painful to recall. Without access to your past, in the Western tradition, your identity is left broken and incomplete. The path to healing goes through the licensed therapeutic professional whose job is to help the individual to come to terms with this trauma by recovering or repairing repressed or broken memories of a still painful past.

In the Chinese case, Dominic believes that it is more helpful to think of trauma in relation to place. It is the experience of being uprooted and torn from one’s ancestral homeland that is traumatizing. It is a trauma experienced by a group or community who might end up being subject to multiple traumas. Through the collective memory work of the community, efforts are made to repair the damage caused by the separation from one’s native place. Memory is never lost or damaged, it is the community that draws selectively from the past to restore the community’s broken or incomplete identity.

Recognizing that memory is not history, Dominic devotes his opening chapter to establishing the historical evidence for the trauma caused by the great exodus. He points out that this trauma was experienced both by mainlander civil war refugees (waishengren) and by native-born Taiwanese (benshengren) subjected to this wave of displaced people. From personal stories and interviews with mainlanders exiles to recently declassified government documents and contemporary newspaper ads, Dominic draws from a variety of sources to convey the impact of the great exodus. He references the hundreds of newspaper classified ads searching for missing persons or individuals separated from their families seeking new adoptive parents to convey the dislocation and desperate need for new family connections. He uses records from the Taiwan Provincial Police Administration to underscore the rise in crime and suicidate rates among the refugee population. Minutes from high-level government meetings underscore the pronounced concern about the susceptibility of soldiers to depression and suicide—especially among the unknown thousands kidnapped by the Nationists and forced to serve in the military.

The influx of hundreds of thousands of mainlander refugees who took scarce housing and increased the level of crime and insecurity had an undeniable impact on the native-born Taiwanese population. But just as the descendants of mainlander refugees choose to omit these repercussions from their memory work on the great exodus, so do native-born Taiwanese. The memories that seem most important to native born Taiwanese are those of the 228 Incident and the White Terror when the newly installed Nationalist goverment brutally suppressed popular resistence by what Dominic describes as the “semi-Japanized Taiwanese elites.” There is little doubt, however, that the presence of thousands of renegade and often unruly soldiers created a climate of fear and insecurity—especially after decades of order and stability under Japanese rule.

Turning to the memory work of mainlander refugees, Dominic notes that the experience of the great exodus was not aired publicly until the 1980s. This was largely due to political suppression. The goal of the Nationalist regime was to return and retake China. Dwelling on traumatic memories of the defeat and the trauma of the great exodus would only highlight the shame and humiliation of having lost the civil war.

But beyond government suppression, Dominic argues that the memories that were most meaningful to mainlander exiles during the 1950s were sojourner memories from the Great Resistance War against Japan. These memories became salient in the 1950s because they recalled an earlier time when the mainlander refugees community was also displaced from their native homes. These were comforting memories because they offered the reassurance that the stay in Taiwan would also be temporary and they would eventually be able to return home. Memories of wartime sojourning, Dominic finds, were pervasive during the 1950s in a wide variety of non-fiction writings from travelogues and essays to self-reflective pieces on daily life.

History is not a panacea for curing historical traumas. Yet, the possibility of finding empathy, reconciliation, and an approach to transitional justice agreeable to communities and nations torn apart by painful memories arises from a historically informed understanding that puts these memories in proper perspective. Dominic Meng-Hsuan Yang, The Great Exodus from China: Trauma, Memory, and Identity in Modern Taiwan.

This mentality of wartime sojourning, Dominic explains, can also help us understand what he describes as the “unholy alliance” between the mainlander refugee community and the ruling Nationalist government. While this alliance often goes unquestioned from the outside, there were deep rifts of suspicion between the two sides. Unknown thousands of soldiers, Dominic reminds us, were abducted and forced to serve in the Nationlist army. Large numbers of these soldiers found themselves exiled in Taiwan, far from their families and unable to return home for decades. Low pay, political suppression, and corruption only added to the resentments toward the Nationalist regime. The Nationalist government was equally suspicious of the political loyalties of the unvetted thousand of exiles who flooded into Taiwan after the Communist victory in 1949. Dominate notes that while mainlander refugees represented only 10-15% of Taiwan’s population, they accounted for over 40% of the victims of state violence. It was the powerful longing to return home, and the sentiment that the Nationalist regime was the only and best chance of realizing this dream, that resulted in this unholy alliance.

Maintaining these sojourner memories, however, was only possible as long as the Nationalist regime in Taiwan could maintain the illusion that it would indeed return to retake China. After 1958 this became increasingly difficult. In 1958, when fighting once again resumed between Mao’s forces and Chiang’s troops still occupying islands near the coast of the Fujian Province, US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles flew to Taipei to meet with Chiang. In return for US support Dulles demanded that Chiang would not escalate the current crisis or attack the PRC in the future without consulting Washington first. In what became known as the American Joint Communiqué of 1958, Chiang Kai-Shek publicly acknowledged that henceforth political means, not force, would be used to resolve differences with China.

It was from the 1960s to the mid-1980s, that we see the emergence of a second memory regime which Dominic labels as cultural nostalgia. At the heart of this period of cultural nostalgia was the proliferation of native place associations. Organized around shared places of origin, members of native place association drew largely from memory to collect everything from songs and poems to recipes and folklore. Members devoted considerable sums, in some cases their entire life savings, to finance bulletin and reference magazines to circulate this information with the hope of transmitting their culture to the next generation and to reduce the guilt that came from what Dominic describes as the “social trauma of the diminishing hope of return.”

This period was not simply one of nostalgia for a home that most now believed they would never again, it was also about putting down roots in Taiwan. By financing magazines, graveyards or even museums devoted to their places of origin members were also investing significant resources in Taiwan. Dominic notes that some of the associations became deeply involved in local root seeking. They sought out evidence, however thin and unsubstantiated, that ancestors from a much earlier period may have settled in Taiwan. This need to find a genealogy, however fictive and fabricated, was central to the process of repairing the trauma of being uprooted by finding new roots in Taiwan.

The period of cultural nostalgia and native place associations came to an end in the 1980s because of larger political developments in China and Taiwan. Under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping it became possible to return to China. As part of the move to democratization and in response to popular pressure, Chiang Ching-Kuo, who assumed the leadership position in Taiwan after the death of his father, Chiang Kai Shek, decided to end the forty year ban on travel to Taiwan. The work of native place associations was no longer necessary because access to the real native place was now possible.

Despite these developments, Dominic notes the return home was still long and extremely difficult. Because Taiwan, or the Republic of China, still did not recognize Communist China, or the Peoples’ Republic of China, it was necessary to travel through places like Hong Kong or Japan. This, and the need to bring gifts for family and relatives, added to the extremely expensive cost of the trip. But the most difficult part of the return home was acknowledging the existence of wives and children in China to their families in Taiwan. Before returning home, mainlander refugees had to come clean to their families in Taiwan about the truth of the families in China.

Despite all of these difficulties the greatest shock came when the returnees finally reached their native places only to discover that everything had changed. Family and relatives who remained in China and lived through the Mao years had internalized a very different set of values, concerns, and even forms of speech. The importance of ancestor worship, a central preoccupation of returnees, had come under attack during the Mao era as a form of superstition. Many family tombs were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. Moreover, relatives of mainlander exiles who remained in China, suffered disproportionately during the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution because of their ties to a population of perceived traitors and enemies of the state. After the initial shedding of tears when mainlander exiles reunited with family and relatives after decades of forced separation, the expectation that those who remained in China would be compensated soon followed. Strained family relations combined with now unrecognizable native places resulted in a profound trauma, the trauma of the return home.

This trauma was compounded when the returnees came back to Taiwan only to find that they had now become a resented and suspect minority. As Taiwan began to go through the process of democratization it was natural that mainlander refugees and their children, long associated with the nationalist regime, would be regarded as a privileged minority responsible for the injustices experienced by native-born Taiwanese. At the very moment that mainlander refugees were ready to embrace Taiwan as their home they now had to fight for their place in Taiwan.

It was at this particular juncture that memories of the great exodus, suppressed publically for forty years, finally surfaced. These memories were evoked not by the first generation but by their children and grandchildren. These later generations had never identified with the older generation’s native place association. As early as the 1970s younger generations began to take up their own memory work, focusing on the people and places that were most meaningful to them. Their focus was on the impoverished and poorly treated old military veterans they had come to know during their military service. In response to urban renewal plans that threatened to level the places where they had grown up, they also took a particular interest in the preservation of military family villages. Originally planned as temporary accommodations by the nationalist regime for soldiers and their families, they became long term places of residence. Central to the memories and connection to Taiwan of the generations raised there, many have been converted to museums. Perhaps the most prominent example is Sisinan Military Families’ Village located close to Taiwan’s landmark building, Taipei 101.

It was within the particular context of the trauma of the return home, followed by the trauma of the return to a Taiwan that now regarded them as a suspect minority, that younger generations of mainlander exiles merged their earlier memory work into stories about the great exodus. The outpouring of memories of the great exodus at this very moment, Dominic asserts, was for later generations of mainlander exiles to lay claim to Taiwan as their home. This claim was based on the assertion that their families came to Taiwan as refugees, just as most Taiwanese came as migrants, and that they have just as much of a right to see Taiwan as their home.

Given Dominic’s focus on the traumas that shaped the memories of mainlander exiles and their descendants in Taiwan one might conclude that he is a member of this community. Only at the end of his book does he reveal that his ancestors migrated to Taiwan during the Quing Dynasty and that his family suffered from the Nationalist government. He, like many other members of his community, harbored deep resentments and misgivings about the mainlander population in Taiwan. For Dominic, the value of his personal journey in writing this book is how it helped him develop a degree of empathy for mainlanders in Taiwan. While he has no illusions about the possibility of long embattled communities finding common ground through a shared understanding of their traumatic experiences, he is convinced that an informed historical perspective can help. It was through his own archival research that he came to appreciate the very real nature of trauma experienced by the mainlander population and the therapeutic role of memory. Rather than simply dismissing memory as selective and self- serving, an historical awareness can help us understand why another community remembers the past in its own way. History may not cure historical traumas but it may be an important means of fostering empathy and moving towards reconciliation.*

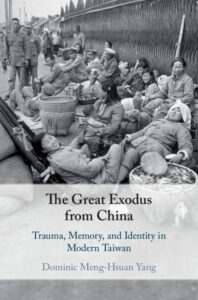

Photo: At Shanghai North railway station, 1949. Photo courtesy of Virtual Cities Project (Institut d’Asie Orientale, Lyons, France).

*My interview with Dominic took place on November 8, 2021.

Dominic Meng-Hsuan Yang

Dominic Meng-Hsuan Yang is associate professor of history at the University of Missouri. He is the author of The Great Exodus from China: Trauma, Memory, and Identity in Modern Taiwan.