Over a decade of civil war tore apart the tiny Central American nation of El Salvador. Throughout the 1980s the United States poured billions of dollars into the conflict to stop the spread of communism in Central America. Beyond the massive loss of life and even greater human displacement, deathsquads and special military units massacred, tortured, and disappeared civilian populations caught in the crossfire. When a peace agreement was finally reached in 1992, all sides agreed to a general amnesty. There would be no trials, no effort to identify the perpetrators of human rights abuses or war crimes. Yet beginning in the 1990s, El Salvador experienced an unprecedented outpouring of personal accounts of the war from the former participants. Furman University historian Erik Ching, author of Stories of Civil War in El Salvador: A Battle Over Memory, tells us what we can learn from these accounts about the civil war and those who fought it.

Two-thirds the size of Belgium or roughly equal to Massachusetts, El Salvador became one of the world’s top five coffee producers by the early twentieth century. Grown at high elevations on volcanic slopes, it was its rich soil that was the source of El Salvador’s coffee growing wealth. However, two of three main coffee producing regions were occupied by peasant communities who had lived there since the time of the Spanish empire. Moreover, many of these communities had sizable indigenous populations. The story of the rise of El Salvador’s coffee industry is one of the expropriation of this land from the people who had lived there for centuries. This process began in the 1880s with a series of decrees that abolished all communal landholding.

As it reached its coffee producing zenith, most agricultural land in El Salvador was held by a small number of elite families. As with many other Central American states, El Salvador became a mono crop economy relying on coffee for 90% of its exports. The wealth of this economy benefited only a minute elite segment of society with a growing peasant and often indigenous population reduced to the status of rural laborers. To safeguard the status quo elites relied increasingly on coercive means. Large number of local men were recruited to police the population. After an extremely brief period of reformist government that lasted only nine months in 1931, the military seized power and would remain in power for the next fifty years. The first of these military rulers, General Maximiliano Martínez, set the brutal precedent for how El Salvador’s military governments would respond to rural protests for reform. When peasants rose up in rebellion in 1932 in western El Salvador the government responded with massive bloodshed. Within a two week period thousands, and perhaps tens of thousands, were killed in what became known as la Matanza (the Massacre).

Efforts to promote land reform or industrialization in El Salvador that would alleviate the problems of rural poverty alway met too much opposition from landed elites to achieve meaningful change. Despite their greater willingness to experiment with reforms, military regimes continued to rely more on brute force to maintain order. During the 1960s and 1970s the military leadership created a 100,000 strong, largely peasant manned, paramilitary force called Organización Democrática Nacionalista or ORDEN to quell dissent in the countryside. Whatever hopes for peaceful reform that may have remained were crushed in 1972 when military leaders resorted to massive electoral fraud to steal the presidential election from José Napoleón Duarte, head of a coalition of centrist and leftist parties. Historian Erik Ching notes that it was the stolen 1972 presidential elections that was most often cited by former guerillas as the reason why they abandoned all hope for peaceful change and decided to take up arms against the government.

Five militant organizations took shape by the 1970s, three with roots in or directly connected to El Salvador’s Communist Party. All of these organizations were originally urban-based. It was the links they formed with the rural population, beginning in the mid-1970s, that allowed them to tap into a much broader base of support. The final event that allowed for the start of the civil war was the unification of these organizations in 1980 into the Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (FMLN)—named after, Farabundo Martí, one of the leaders of the 1932 revolt and a founder of the Communist Party in Central America. One of the more impressive features of the civil war, argues Ching, was the ability of these disparate organizations to maintain a united front against the Salvadoran army for over twelve years.

Although guerilla forces had been fighting the army for years, the civil war in El Salvador did not formally begin until January 1981. The plan for a quick victory was based on the success of the Sandinistas in Nicaragua and Castro’s forces in Cuba. An all out attack on the army would trigger a popular uprising that would topple the regime. Fully aware of Ronald Reagan’s campaign promise to take a tough stand against the spread of communism in Central America, the offensive was planned to begin before Reagan took office in January 1981. However, the January offensive failed to trigger the hoped for mass uprising and the insurgents were unable to match the strength of the Salvadoran army. As a result, the guerillas retreated to their respective strongholds and what was originally conceived as a quick victory became a prolonged war of insurgency in the countryside.

Guerilla efforts to expand their areas of control succeeded for the first few years of the war. However, with growing US support, the Salvadoran army was revamped to meet the new guerilla threat. In addition to expanding in size, new elite battalions were created to hunt down and neutralize guerrilla resistance. The most infamous example was the Atlacatl Battalion, trained by US military advisors at Fort Bragg in counterinsurgency tactics. It was the Atlacatl Battalion, notes Ching, that was responsible for many of the worst human rights abuses during the civil war—most notably at El Mozote in December 1981 where over a thousand civilians were killed in a single day.

The guerillas also had their own special forces units, such as the Rafael Arce Zablah Brigade (BRAZ), and were able to beat back the army until they controlled 25% of the territory in 1983. However, it was in this same year that the Reagan administration dramatically ramped up its support for the Salvadoran government. This support included advanced weapons systems, fixed wing fighters, and attack helicopters. The insurgents responded by disbanding larger fighting units like the BRAZ and adopting smaller hit and run tactics hoping to exhaust government forces in a war of attrition. As each side sought ways to counter the other, the fighting stretched out for years. It was the ability of the insurgents to smuggle tons of munitions and food into the country, despite US ships patrolling Salvadoran shores and the use of US surveillance aircraft and satellites, that allowed them to stay the course for over a decade.

In the face of the existence of these four memory communities, and their mutually exclusive renditions of the war, one cannot help but wonder how stable postwar El Salvador can be, particularly in the face of so many destabilizing pressures, such as economic stagnation, gang violence, drug trafficking and out migration. Erik Ching, Stories of Civil War in El Salvador: A Battle Over Memory.

Just as the war seemed to reach a stalemate, Ching notes that four developments brought all sides to the peace table. The first was a Tete style offensive, in November 1989, when the insurgents showed that they still had sufficient means to take the fight to the heart of the capital of San Salvador. The military’s brutal handling of the attack—carpet bombing poor neighborhoods and assassinating six Jesuit priests at the Universidad Centroamericana José Simeón Cañas (UCA)—caused international outrage. Second, the guerrillas acquired surface-to-air missiles which significantly diminished the government’s control of the skies. Third, the Cold War came to an end, eliminating the most important motive for US involvement. Fourth, the Sandinistas were voted out of office in Niguaga in 1990, removing a key ally for the guerillas. It was these four factors, argues Ching, that drove all sides to the bargaining table.

The peace deal that was reached required the FLMN to disband its army, turn over its weapons, and transform itself into a legitimate political party. The Salvadoran army, in turn, was downsized and the military branches most implicated in human rights abuses were dismantled. The national police was also restructured to include some elements of the FMLN. Despite these significant changes, there was no major landform or structural changes to the economy. While El Salvador successfully transitioned from a military regime to a democracy, the decision was made not to pursue any kind of process of truth and reconciliation. A general amnesty law was passed which made it impossible to adjudicate the crimes of the past.

In the absence of any court of law to examine the past, Ching argues that Salvadorans seem to have opted to make their own case to the court of public opinion. Shortly after the war, Ching notes that there was an explosion of memoirs and testimonials about the war produced by the former combatants. These accounts, Ching adds, were completely unprecedented in El Salvador..

Intrigued by this outpouring of memories, Ching examined thousands of pages of these accounts to see what they revealed about the war and those who fought it. Ching was surprised that the accounts fell neatly into the four major groups who participated in the war—civilian elites, military officers, guerilla commanders and rank and file soldiers. While each of these groups exhibited a striking uniformity, what surprised Ching were the divisions that became apparent between former allies in the conflict.

The accounts of civilian elites and military officers demonstrated pronounced sentiments of mutual suspicion and distrust. Civilian elites distrusted what they regarded as the reformist inclinations of military officers and their lack of commitment to the liberal economic order. Military officers, they feared, would be all too willing to sacrifice the economic interests of the civilian elites in order to maintain the peace. Military officers saw civilian elites as too deeply entrenched in the desire to preserve their wealth and privilege. In their opinion, it was the unwillingness of political elites to support much needed reforms that was the source of rural resentment and unrest. The accounts of civilian elites, adds Ching, hardly mentioned the role of military officers in winning the war. Instead, they featured their own political initiatives, like the creation of the ARENA (National Republican Alliance) political party and their privately financed paramilitary forces as being the key contributors to the end of the war.

Guerrilla commanders and their rank and file soldiers were also far removed in how they recalled the war. Guerrillas commanders came from privileged and often sheltered backgrounds. Their accounts were filled with fond memories of comfortable and supportive family life. It was only as young adults, either through the teachings of Catholic liberation theology, or by personally witnessing or experiencing the brutality and violence of the regime that they gradually became politicized and committed to revolutionary action. While Ching stresses that rank and file peasant soldiers were also radicalized by liberationist theology, the only accounts available to him exhibited a very different perspective on the war. Rank and file testimonials—transcribed oral accounts from largely illiterate peasant fighters—cast their decision to go to war not as the product of a gradual political awakening but rather the inescapable response to a conflict that came to their communities.

These four memory communities, as Ching labels them, also had very different views on the final outcome of the civil war. Guerrilla commanders tended to be the most optimistic. They pointed to the very real achievement of bringing an end to military rule and establishing a functioning democracy in which they became key participants. The response of civilian elites was somewhat mixed. While they were grateful to have preserved their personal holdings and the liberal economic order, they were uneasy about the new climate of violence and insecurity in El Salvador. Military officers voiced their pride in their twelve year fight on behalf of the defense of the nation and their success in preventing the guerillas from toppling the government—although many remained convinced they could have won the war. Rank and file peasant guerillas soldiers were the most pessimistic in their views on the outcome of the war. They had fought for fundamental structural reforms to the economic order. These reforms never happened. While their commanders were able to return to their privileged lives, the disbanded peasant soldiers faced an even more impoverished and insecure future.

Years after the end of the civil war in El Salvador the fight continues to rage through the memoirs and testimonials of the former combatants. The outpouring of these personal accounts demonstrates the need and desire of Salvadorans to confront the past. Cloistered into their own respective memory communities, there is little opportunity for the kind dialogue that might build trust between these important segments of Salvadoran society. As Erik Ching makes abundantly clear, these accounts are replete with sentiments of distrust and suspicion. There is still little desire to shed light on the crimes of the past and much pessimism remains about the outcome of the war. With El Salvodor’s recent turn toward authoritarian rule the prospects for a peaceful resolution to the nation’s unfinished memory wars look increasingly bleak.*

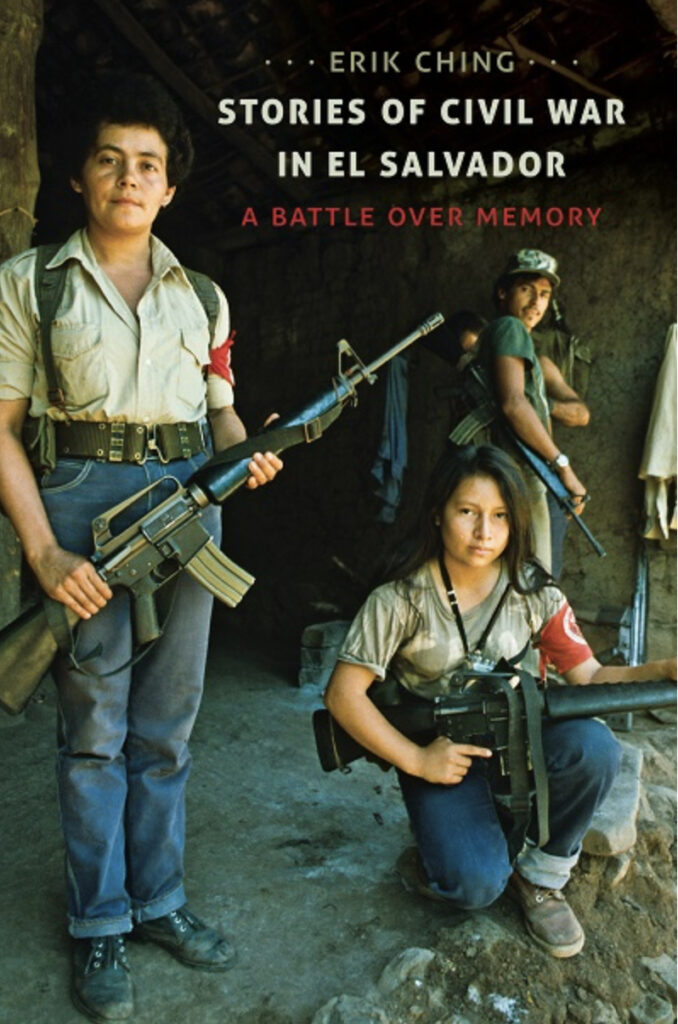

*I would like to thank the Museo de la Palabra y la Imagen in San Salvador for allowing me to use some of the photos from their rich collection on the civil war in El Salvador. I would also like to thank the Google El Salvador Studies Working Group for sharing suggestions on the additional resources below:

- For a list of books, films and additional educational resource on Central America see Teaching Central America.

- See this link to the Spanish language version of the British filmmaker Richard Duffy’s documentary, The Past is Not History, on the community of Arcatao, El Salvador, hard hit by state violence during the 1980s and 1990s.

- Filmaker Patricia Goudvis’ film from the early 1990s, If a Mango Tree Could Speak, looks at the wars in Central America from the perspective of children. Also see her related website, When we were young, there was a war.

- A recent issue of the on-line journal Realidad features a number of articles on memory and El Salvador.

- For another perspective on memories of the civil war see Mike Anastario’s Parcels: Memories of Salvadoran Migration.

Erik Ching

Erik Ching is the Walter Kenneth Mattison Professor of History, Interim Associate Provost for Engaged Learning and Director of Undergraduate Research at Furman University. He is the author of Stories of Civil War in El Salvador: A Battle Over Memory, Authoritarian El Salvador: Politics and the Origins of the Military Regimes, 1880-1949, and Remembering a Massacre in El Salvador: The Insurrection of 1932, Roque Dalton, and the Politics of Historical Memory (with Hector Lindo-Fuentes).